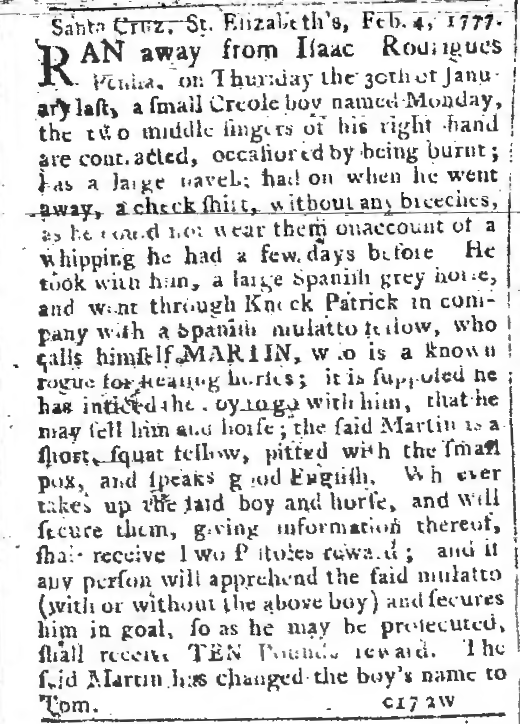

In just two hundred words a newspaper advertisement tells us virtually all that we know of the escape of an enslaved boy in Jamaica in February 1777. His name was Monday and he had escaped from Isaac Penha on January 30th, 1777. Penha came from Santa Cruz, a small town in St. Elizabeth, Jamaica, located in the southwestern region of the island. Though the precise circumstances of Monday’s escape are unclear, the advertisement hints indicates that a free man may have aided this young boy’s escape. However, while this companion may have been critical to Monday’s escape, this boy may well have had his own reasons and objectives in escaping: perhaps he sought to reunite with family or friends, or maybe he was desperate to get away from his enslaver. Whatever the circumstances of or motivations for Monday’s escape, his decision to break free in Britain’s leading plantation colony was extremely courageous.

Although most enslaved people in Jamaica worked on plantations and pens, it is more likely that Monday’s enslaver was a merchant. The name Penha has Portuguese origins and is also tied to the Jewish community. Though the Jewish community wasn’t very prominent in the transatlantic slave trade, they played a large role in the buying and selling of slaves and the crops produced by slaves in local Jamaican slave markets. Furthermore, Penha’s location in a town suggest that Monday was likely involved in a more domestic kind of labor, or perhaps work in a merchant’s shop or storerooms. His duties may have ranged from cooking and cleaning, working as a personal servant or valet, and perhaps manual labor associated with trade. Monday’s youth meant that Penha probably purchased him at a lower cost. Perhaps Monday was purchased from a local merchant or planter, and if so he may at that point have been separated from his family. Whenever this separation occurred it would have been traumatic and life-defining. It may also have motivated him to flee from Penha.[1]

Perhaps Monday turned towards the Black community for help in his escape. Jamaica’s enormous community of enslaved people did not readily conform to the boundaries of White-constructed plantations or parishes. Although thousands of enslaved families in Jamaica were split up, enslaved and some free people in Jamaica worked hard to nurture relationships across space and between plantations and towns. Their social network transcended boundaries implemented by their White oppressors, although enslavers made it as hard as possible for enslaved people to communicate. It is therefore plausible to think that the Black community in and beyond the Penha residence may have been critical in Monday’s escape, or at least an inspiration to him. Perhaps this community provided him with help to reunite him with loved ones.

However, this network was not the only thing that connected Monday with his family. Akan people in West Africa regularly used day-names as part of the appellation of new-born children: Kojo was one of the names applied to male children born on Monday, and perhaps Monday’s parents were Akan-born people who had anglicized a traditional African familial naming tradition.[2] The advertisement indicates that Monday was a “Creole boy,” and he had clearly been born into slavery in the New World. Perhaps Monday’s mother was Akan, and she kept this tradition alive while utilizing an English rather than an Akan word.

In his advertisement Penha suggested that Monday had been aided in his escape by a “known rogue” known as Martin, a “Spanish mulatto” who was almost certainly a free man. This raises questions regarding Martin’s motivations and the nature of the relationship between him and Monday. We can only guess at Martin’s motivations. Perhaps he was moved to action by Monday’s youth and vulnerability, and was trying to help the young boy escape to family and friends, or create a new life for himself. On the other hand perhaps Martin took advantage of Monday’s youth and naivete to entice him away from Penha, intending to steal the boy and treat him as his own enslaved property, or perhaps to sell him to another enslaver. The advertisement reveal the horrific whipping that Monday had received some days before his escape, a whipping so harsh that he couldn’t wear breeches. Moreover, the contraction of Monday’s fingers due to a burn may have been further evidence of the violent and abusive environment this young boy was living in. Perhaps seeing the effects of this violence on young Monday had inspired Martin to save the child no matter the risk. Whatever Martin’s intention, Penha believed that the pair were headed east.

Penha indicated that Monday and Martin were headed through Knock Patrick, a daunting 20-mile journey from Santa Cruz. The two had stolen a large horse , and this may have aided both in their journey away from Santa Cruz. Traveling through the densely wooded rainforest may have concealed their identity and intentions, providing at least some cover for them to maneuver during the day. Travel by night along Jamaica’s primitive roads and tracks was difficult and dangerous, and unless moonlight penetrated the forest canopy or illuminated the roads through plantations they would have been on total darkness. And at any point, the two might be challenged by White men or patrols and taken into custody. Escape was extremely difficult, and perhaps the lack of a subsequent advertisement may indicate that Monday was not free for long. But it is possible he was able to remain free, at least for a while, perhaps even reuniting with family and friends. Whatever the outcome, and whatever Martin’s motivations, Monday’s decision to escape was brave, born of pain and resentment at his ill-treatment.

View References

[1] Nuala Zahedieh, “Defying Mercantilism: Illicit Trade, Trust, and the Jamaican Sephardim, 1660–1730,” The Historical Journal, 61 (2018), 77–102.

[2] David DeCamp, “African Day-Names in Jamaica,” Language, 43 (1967), 139-49; Vanessa Danso, “The Akan Day Names and Their Embedded Ancient Symbolism.” Modern Ghana, Modern Ghana, 14 Feb. 2016, www.modernghana.com/lifestyle/8691/the-akan-day-names-and-their-embedded-ancient-symbolism.html