Any relief New Englanders might have felt at Parliament’s repeal of the Stamp Act had swiftly disappeared in the face of the Declaratory Act (1766) and the Townsend Acts, which went into effect on November 20, 1767. Going far beyond the original Stamp Act, these new laws sought not only to raise taxation in the colonies but to use this revenue to fund an imperial government that would be independent of colonial assemblies. Bostonians led the way in organizing protests against these new measures, and on November 30 the front page of the Boston Gazette began with a letter by John Hancock and six other leading Bostonians encouraging a strong but peaceful response. This was followed by a letter from James Otis, clarifying remarks he had made at a recent town meeting, and an anonymous letter to Boston’s merchants signed by “LIBERTY,” begging their assistance “to ward off the blow, that every moment threatens me with certain and eternal death.” Articles about or references to the imperial crisis and brewing colonial resistance appeared on each of the newspaper’s four pages.

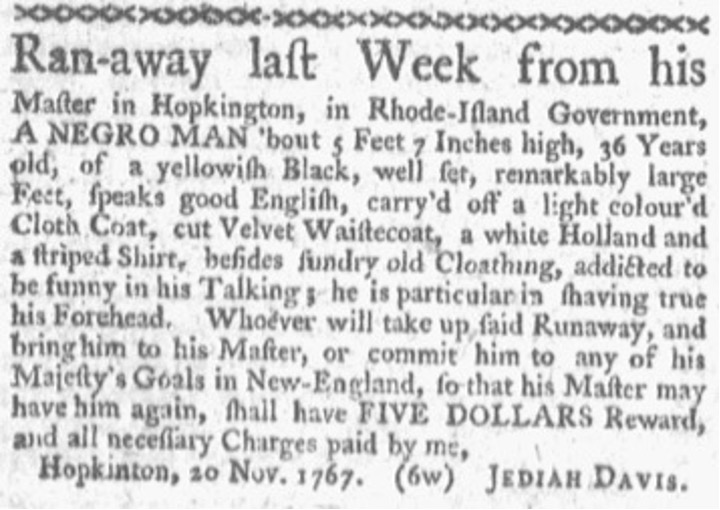

But one of the advertisements on the back page referred to a very different assertion of liberty by an unnamed man who had escaped from his enslaver in Rhode Island. We do not know this man’s name, or anything about him other than what is contained in this short advertisement. His enslaver, Jedediah Davis, wrote that the freedom seeker “speaks good English,” which suggests that the man may have been African-born. A thirty-six year-old man who had been born and raised in the colonies would have had English as his first language. He took with him a mixture of good quality and old clothing, including a velvet jacket and two shirts: perhaps he had taken some of his enslaver’s clothing, either to present himself as a smartly-dressed free man, or perhaps to sell or trade to ease his escape.

Davis also commented on more personal characteristics of the freedom seeker. According to Davis this man was “addicted to be[ing] funny in his Talking,” suggesting that the freedom seeker constantly joked or used humor in his interactions with others. Was this a reflection of the man, an indication of a genuinely humorous disposition? Or was it a defense mechanism, a way for an enslaved man to deflect attention away from himself, causing his enslaver and other White men and women with power over him to smile, laugh, and relax? White Americans often made fun of and ridiculed Black Americans, but it was possible for enslaved people to then use White racist stereotypes to create a kind of protective shield. White people saw what they expected to see, a humorous Black man, joking and unthreatening, and what the man actually thought, felt, and believed remained hidden. There could be protection in humor. There could also be power in laughter, of a sort. Enslaved folk might use oblique humor to critique and undermine their enslavers and White society and culture more generally.[1]

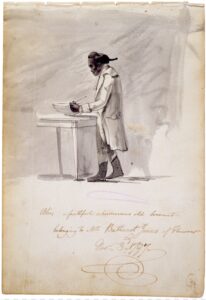

This advertisement contained a second reference to a particular characteristic of this freedom seeker, noting that “he is particular in shaving true his Forehead.” This phrasing suggests that the unnamed man shaved the front part of his head, while allowing the hair at the sides and back to grow longer. It is possible that this is further evidence of this man being African-born, as the practice of shaving the crown of the head was not unusual in West Africa. For example, the “Coromantee” man Alleck who escaped in 1786 “commonly shaves the fore part of his head.” Distinctively West African hairstyles became part of an African American culture, and over time American-born Black people adopted shaved foreheads and other hair styles, as in the case of a Virginia “Muatto Man named Syphax” whose enslaver described him as having “the fore Part of his Head shaved, and the back Part has long Wool.”[2] Benjamin Henry Latrobe’s sketch of Alic, an enslaved man in the Virginia home of Bathurst Jones, provides a sense of how this hairstyle might have appeared, although not all who shaved their foreheads in this fashion would have had their hair tied at the back in a braid or queue.

What might this distinctive hairstyle have meant to the man who escaped from Jedediah Davis in 1767? Often Africans who were loaded onto slave ships had their heads completely shaved, an act that stripped away the culture and identity inherent in distinctive hair styles. Yet as it grew back their hair provided enslaved people with a form of personal adornment and self-expression that was one of the few means available to them to express individuality and culture, whether that of their African birth societies or of their developing culture in the Americas.[3]

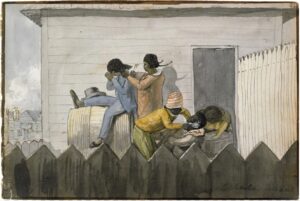

Another artwork by Latrobe gives a sense of the ways in which hair styles might matter to enslaved people. In addition to showing particular fashions, Latrobe communicated the care with which these people prepared their own and their friends’ hair. Slavery was inscribed on the bodies of men, women, and children, in the form of whip scars, inferior clothing, brand marks, and the deleterious effects of often back-breaking labor. Hair provided one way in which the enslaved might take some control of their appearance and assert personal and broader cultural identities. Moreover, as Latrobe’s watercolor painting illustrates, hair styling might be a communal activity, a social ritual in which African American culture was taking shape.

The Rhode Island census of 1774 recorded Jedediah Davis as the head of a household of thirteen people, one of the largest in the community, including three indigenous and one Black man. Was this the same man who had attempted to escape seven years earlier, or was this a different enslaved person? We cannot know. But we do know that the man who eloped in 1767 was a man who laughed and used humor, possibly as a defense mechanism but maybe because it reflected his personality. Moreover, his hairstyle showed this man defining himself as best he could, with pride in his distinctive appearance. As the revolutionary crisis deepened, daily life went on, with laughter, proud self-adornment, and escape.[4]

View References

[1] For discussion of some aspects of this, see Dexter B. Gordon, “Humor in African American Discourse: Speaking of Oppression,” Journal of Black Studies, 29 (1998), 254-76, and Lawrence W. Levine, “Black Laughter,” in Levine Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro-American Folk Thought From Slavery To Freedom (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 298-366.

[2] August, Georgia State Gazette, or Independent Register (Augusta), December 22, 1786; “Middlesex County, Virginia… RAN away last Night… Syphax,” Maryland Gazette (Annapolis), November 15, 1752.

[3] See Shane White and Graham White, “Slave Hair and African American Culture in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries,” The Journal of Southern History, 61 (1995), 45-76; Diane Simon, Hair: Public, Political, Extremely Personal (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000).

[4] Entry for Jedediah Davis, Hopkinton, Rhode Island in Census of the Inhabitants of the Colony of Rhode Island and providence Plantations, Taken By Order of the General Assembly, In The Year 1774, arranged by John Bartlett, (Providence: Knowles, Anthony & Co., 1858), 221.