On 16 November 1776, Isaiah Robinson, captain of the Andrew Doria, sailed into Oranjestad, the capital of St. Eustatius, a Dutch Caribbean colony. Seeking to purchase weapons and gunpowder for the United States and flying the flag of the Continental Congress, Robinson fired a thirteen-gun salute, one for each of the newly independent states. St. Eustatius’s governor Johannes De Graff ordered Oranjestad’s fort to return an eleven-gun salute, properly acknowledging a fellow nation. This moment—the “First Salute”—was one of the earliest and most prominent recognitions of a sovereign United States by a foreign power.[1]

Fourteen months later, on 6 January 1778, Polydore, an enslaved sailor serving under Robinson, who now commanded the trading sloop Polly, made his own first salute to freedom. Polydore absconded from Robinson while the Polly was in Christiansted, still colloquially known as “Bass-End,” the capital of St. Croix, an island in the Danish West Indies. Polydore’s reasons for absconding are unclear, but Robinson believed that Polydore’s wife harbored him, suggesting Polydore sought to spend time with his spouse. Some might see Polydore’s strike for freedom as less consequential than the “First Salute,” but it was no less emblematic. His story reaffirms the possibilities this revolutionary moment offered for enslaved people to seek their freedom, especially highly-mobile, highly-skilled men like Polydore.

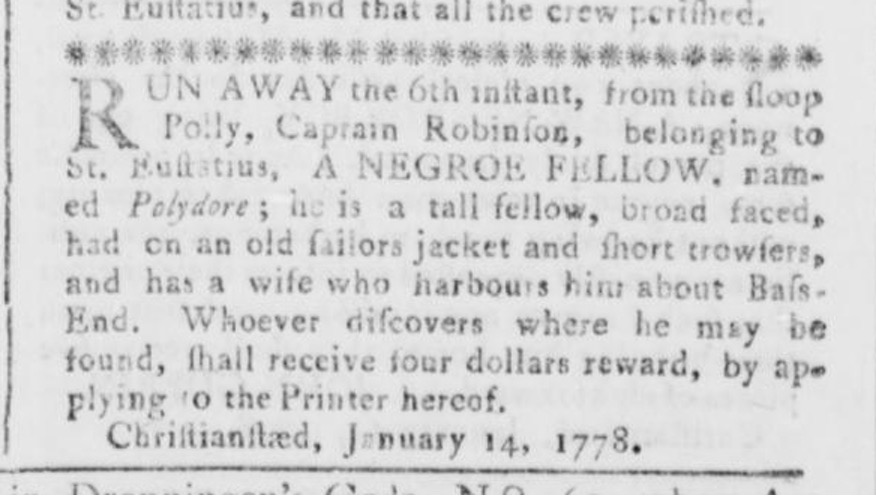

Very little is known about Polydore. Nevertheless, the advertisement offers clues that allow us to better understand his life. Polydore was a “tall fellow” with a “broad face” who wore an “old sailors jacket” and trousers when he escaped. The mention of Polydore’s wife means he was old enough to have one—that is, perhaps, in his late 20s or 30s. Likewise, he “belong[ed] to St. Eustatius.” Robinson hired Polydore, a resident of the Dutch colony, to work onboard the Polly. The timing of the advertisement is curious. Robinson noted that Polydore disappeared on 6 January 1778, but did not publish the advertisement until 14 January. The advertisement also appears at the very end of the second page of the 14 January issue of The Royal Danish American Gazette. Robinson may have hastily placed the advertisement after failing to locate Polydore. By that time, Polydore could have already departed the island or disappeared into Christiansted’s free Black community.

Polydore was important for Robinson’s trading mission. This region of the Caribbean, known as the Leeward Islands, comprised an “inter-imperial microregion.” Despite multiple empires—Spanish, English, French, Dutch, and Danish—colonizing the area, boundaries mattered little. Islands in this region, such as St. Eustatius and St. Croix, were tied together through intermarriage, interregional migration, and business connections.[2] Sailors, especially enslaved sailors like Polydore, transported goods, people, news, rumor, and gossip between the islands. Isaiah Robinson, himself familiar with the region, would have sought a knowledgeable hand like Polydore to serve on the Polly.

Polydore’s occupation as a sailor is central to understanding him. As abolitionist, author, and formerly enslaved sailor Olaudah Equiano quipped, “it was a very dangerous thing to let a negro know navigation.” Polydore had a marketable, useful skillset in the maritime world of the Leeward Islands. The nature of seafaring also meant he experienced a rough equality, on the high seas at least, with white sailors as they were all dependent on one another to survive the voyage. Polydore would also have been knowledgeable about the Caribbean and have had connections in port cities across the region. And, he was imminently employable, giving him opportunities to abscond and escape any situation he did not like. Finally, as a prominent scholar of Caribbean slavery has demonstrated, “sailor Negroes” also played a “vital role in spreading rumor, reporting news, and transmitting political currents” during the Age of Revolutions.[3]

Polydore seems to have absconded to visit his wife. She lived in the town of Christiansted, St. Croix’s capital. Although governed by the Danes, most European-descended people who lived on the island—two-thirds of the white population—were Anglophones. So many Anglos inhabited the island, in fact, that its newspaper, the Royal Danish American Gazette, was printed primarily in English. The printer did not even own Danish typeface.[4] Many of those Anglophones were from North America or had connections to the mainland, explaining why Robinson was on a trading voyage there.

The vast majority of residents on St. Croix, however, comprising over 90% of the population in 1770, were of African descent. Christiansted too, was overwhelmingly Black, with a population of 2,364 enslaved people, 290 freed people, and 944 whites in 1775.[5] Enslaved people in Christiansted were mostly artisans and, likely in the case of Polydore’s wife, domestics. They were central to the island’s economy, especially overseas trade. There was also a vibrant urban Black community, one capable of hiding Polydore for as long as Robinson hunted him, a point Robinson made with frustration in the advertisement when he complained Polydore’s wife “harbours him about Bass-End.”

Unfortunately, we know next to nothing about Polydore’s fate. However, one thing is clear: Robinson did not apprehend him immediately. Three days after publishing the first advertisement, Robinson had it printed again, and then a third time on 21 January 1778. When Robinson departed the island sometime in late January, it is unclear if Polydore was with him. Perhaps Polydore avoided Robinson entirely. If, though, he was apprehended and forced back aboard the Polly, Polydore would have experienced the same fate as the captain. Robinson took his ship to North America, allegedly carrying provisions for American prisoners held in British-occupied Philadelphia, but upon the Polly’s arrival, the British arrested Robinson and three crew members. Robinson’s past as a naval officer and gunrunner finally caught up with him. George Washington personally interceded for Robinson’s release, but we do not know if he succeeded in liberating the man.[6] Had Polydore successfully struck for freedom, surely news of Robinson’s arrest eventually reached him. He would have understood the irony of his former captor becoming a captee.

View References

[1] Records in the British Admiralty archives suggest that the Danes on St. Croix made an earlier salute to an American vessel, but this event remains the better known. Sometimes the Andrew Doria is called the Andrea Doria. For more on the “First Salute,” see Barbara Tuchman, The First Salute: A View of the American Revolution (New York: Ballantine Books, 1988) and Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy, The Men Who Lost America: British Leadership, the American Revolution, and the Fate of the Empire (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), Chap. 8.

[2] Jeppe Mulich, “Microregionalism and Intercolonial Relations: The Case of the Danish West Indies, 1730–1830,” Journal of Global History 8 (2013): 73-74.

[3] For the quote from Equiano, information about enslaved sailors, and their role in the Age of Revolutions, see Julius S. Scott, The Common Wind: Afro-American Currents in the Age of the Haitian Revolution (New York: Verso, 2018), 38, 71, 75.

[4] Neville A.T. Hall, Slave Society in the Danish West Indies: St. Thomas, St. John, and St. Croix (Mona: University of the West Indies Press, 1986), 15.

[5] For population figures, see tables in Hall, Slave Society in the Danish West Indies, 5, 88. Urban slavery in Christiansted is the subject of Chapter 5.

[6] Robinson and his arrest were the subject of a series of letters between various Continental officials and George Washington and British General William Howe and Washington. See “To George Washington from Francis Hopkinson, 16 March 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-14-02-0161. This document contains a note with the number of sailors and references to Robinson’s mission to supply the prisoners. See also “From George Washington to Francis Hopkinson, 28 March 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-14-02-0311. For the Howe-Washington Correspondence, see “To George Washington from General William Howe, 19 March 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-14-02-0199; “From George Washington to General William Howe, 22 March 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-14-02-0242; and “From George Washington to General William Howe, 27 May 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-15-02-0243. Washington never received a response from Howe, something he complained about, and the reason why Robinson’s fate is unclear. See “From George Washington to the Continental Navy Board, 11 April 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-14-02-0441 and “From George Washington to the Board of War, 16 May 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-15-02-0127. (Websites last accessed 1 February 2024.)