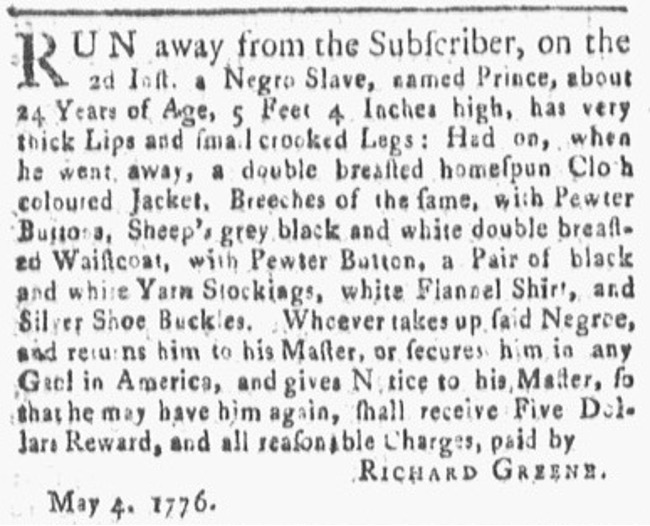

Two declarations of independence were recorded in Rhode Island on May 4, 1776. The first was the Act of Renunciation passed by the Rhode Island Assembly, which dissolved the colony’s ties to Great Britain, renounced royal rule, and created new oaths of allegiance for local officials.[1] The second appeared in The Providence Gazette in the form of an advertisement penned by Richard Greene, in which he recorded that two days earlier an enslaved man named Prince had escaped.[2]

Two years earlier the 1774 Rhode Island census had recorded that the three White people in Richard Greene’s household were served by three enslaved Black people, presumably including Prince Greene. He most likely performed a variety of services for his enslaver, including work on the Greene family farms in Coventry and West Greenwich.[3]

The imperial conflict was personal, dividing families and communities, and it was no different for the Greenes. Richard Greene was inclined to Loyalism, and to the chagrin of his Patriot relatives he would actively support British forces, feeding them information and much-needed supplies. Prince was twenty-four years old when he attempted to seize freedom, a short man with somewhat crooked legs, but well-dressed to reflect the wealth of his enslaver. Richard Greene’s fortunes steadily declined in the wake of Prince’s escape. He was forced to abandon his estate at Potowomut, and separated from his larger family Greene fell ill and fled to British occupied Newport for medical treatment: it was there that he died in July 1779. Prince Greene became a Patriot and a soldier in the Continental army, but the fight for national independence left him maimed and, briefly, in danger of execution.

We do not know whether or not Richard Greene was able to recapture Prince Greene, but if so, the enslaver’s success was short-lived. In 1777 Prince Greene enlisted as a private in the 1st Rhode Island Regiment, effectively combining the effort for self- and national liberation. A year later the Rhode Island Assembly passed a measure that enabled enslaved men to join the Continental Army and commit to serving for the duration of the war. These men’s enslavers would be compensated by the state, while the soldiers themselves would “receive all the Bounties, Wages, and Encouragements allowed by the Continental Congress… and be absolutely free as though he had never been incumbered with any Kind of Servitude or Slavery.” But Prince Greene had enlisted before this law was passed, quite possibly as a self-emancipated man who had escaped from a known Loyalist.[4]

Prince Greene’s new-found status as a free man was confirmed in June 1778 when he married Rhoda Eldred in North Kingston. Rhoda was a free woman of color, and together she and Prince formed their own free family.[5] Did Rhoda accompany Prince as he traveled with the 1st Rhode Island Regiment? Camp followers accompanied the army, including wives and partners who provided essential services including food preparation and medical care. It was a hard life, and disease and malnutrition meant that many soldiers and camp followers died. Prince Greene was one of the few who survived both battle and disease. Soldiers from the regiment fought in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island, and they suffered with the Continental Army during the brutal encampment at Valley Forge in 1777-78.

However, although Prince Greene survived a long term of service in the American army, his service left him scarred in a somewhat surprising fashion. Greene and other soldiers from his regiment were ensconced in a barracks house on the outskirts of Providence when, in the early hours of April 10, 1781, two young men started throwing sticks and stones at the building and abusing the soldiers within. Edward Allen and John Pitcher Jr. were poor White men struggling to survive, and it seems likely that they resented the Black soldiers and free people around them, although the precise reasons for their assault are unclear. After Allen and Pitcher broke through the barracks door the veteran Greene moved to defend himself and his fellow soldiers, loading his musket. The two attackers turned and ran, followed by Greene and some of his fellow soldiers. Greene raised his musket and fired, and his musket ball struck the back of Allen’s head and killed him.

Allen had been running away when he was shot, and perhaps because of the complicated racial and racist politics of the era, Greene was indicted and then tried on a capital charge of murder. A number of local people and army officers testified on his behalf, including his fellow soldier Pero Mowry, a formerly enslaved man from East Greenwich. We do not know exactly what was said at his trial, but we can presume that these witnesses spoke of Greene’s four years of brave service. Their testimony, and his own, led the all-White jury to acquit Greene of murder, but they found him guilty of manslaughter. Pleading benefit of clergy Greene was spared execution, and in open court his right hand was branded with the letter M.[6]

Greene suffered further injury before the war ended. In February 1783 he was a member of an American force of about five hundred men sent to try and capture Fort Oswego on Lake Ontario in upstate New York. The effort failed, and the brutal winter conditions decimated the force. Greene paid a heavy price, suffering “the loss of all the toes and the feet very tender, by means of severe frost,” effectively rendering him an invalid. Now thirty-nine years old both Greene and his nation were free, but he was permanently injured and drawing a monthly pension of $4.[7] The first Federal census of 1790 recorded that Greene was living in East Greenwich, Rhode Island, with two other free persons, perhaps his wife Rhoda and their child. For years he appears to have supplemented his family’s income by playing the fiddle at social events like large quilting parties in the Black community.[8]

Tapping his mutilated feet in time to his music, Prince Greene may have found pleasure as others danced, sang, and enjoyed his playing. And maybe he was able to tell his stories to his wife, and perhaps his children and even grandchildren. He may have recalled his early life in slavery, but his later life and exploits would have surely enthralled his listeners. He had served in the army for much of the War for Independence, earning a badge for long service. Prince Greene had been with General Washington at Valley Forge, and he had served in the harrowing campaign in upstate New York. Did he tell of his trial, showing those who listened the now faded scar of the letter M on his hand? Prince Greene had linked his own freedom to that of the United States, and it seems appropriate that he died on Independence Day in 1819.[9]

View References

[1] Act of Renunciation, May 4, 1776, Rhode Island State Archives, 1/22/19.216 PM. https://sosri.access.preservica.com/uncategorized/IO_71f27fe6-eded-4998-9a7c-a25d68643bf5/ [accessed November 4, 2026).

[2] “RUN away from the Subscriber… a Negro Slave, named Prince,” Providence Gazette (Providence, RI), May 4, 1776. The advertisement was reprinted on May 11 and May 18, indicating that Prince most likely remained free for at least that period.

[3] Entry for Richard Greene, in Census of the Inhabitants of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Taken by Order of the General Assembly, in the Year 1774 (Providence: Knowles, Anthony & Co., 1858), 62.

[4] Act Allowing Slaves to Enlist in the Continental Army,, February 1778, Rhode Island State Archives, https://sosri.access.preservica.com/uncategorized/IO_67bc7f40-035e-4d13-a3d0-96c2d619b123/ [accessed November 13, 2024]. See also Robert A. Geake and Loren M. Spears, From Slaves to Soldiers: The 1st Rhode Island Regiment in the American Revolution Westholme, 2016), 21, 40, 105.

[5] Jacob N. Arnold, Vital Records of Rhode Island. 1636-1850. First Series. Births, Marriages and Deaths. A Family Register for the People. Volume 5, Washington County (Providence, RI: Narragansett Historical Publishing Co, 1894), North Kingston: Marriages, 20. Writing just over half-a-century later, one local historian recorded that the music at quilting and similar parties “was supplied by the violin of an old Negro named Prince Greene”. See D.H. Greene, History of the Town of East Greenwich And Adjacent Territory, From 1677 to 1877 (Providence: J.A. and R.A. Reid, 1877), 54.

[6] A brief account of the trial appeared in the Providence Gazette (Providence, RI), April 21, 1781. For a more detailed account see John Wood Sweet, Bodies Politic: Negotiating Race in the American North, 1730-1830 (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003), 221-4.

[7] “List of Invalids resident in the State of Rhode Island, who have been disabled in the service of the United States during the late War, and are in consequence thereof entitled to receive a monthly pension during life…” (1785), in John Russell Bartlett, ed., Records of the State of Rhode Island And Providence Plantations in New England, Vol. 10, 1784 to 1792 (Providence, RI: The Providence Press Company, 1865), 163. See also Bruce C. MacGunningle, Regimental Book: Rhode Island Regiment for 1781 &c. (East Greenwich: Rhode Island Society for the Sons of the American Revolution, 2011), 53, 67.

[8] Entry for “Green, Prince,” East Greenwich Town, Kent County, in Heads of Families At the First census of the United States Taken in the Year 1790. Rhode Island (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1908), 13. Greene’s purchase of violin strings (and his occasional payment for these and other goods with “1 evening fidlen” were recorded in the Account Book of Almy & Brown, Providence, vol. 67, 1785-90, Rhode Island Historical Society (referenced in Joanne Pope Melish, Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and “Race” in New England, 1780-1860 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998), 242.

[9] George Washington created badges for Continental Army soldiers who had served for three or six years. See George Washington, General Orders, 7 August 1782, Record for Prince Greene, Rhode Island Historical Cemeteries, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-09056 [accessed November 13, 2024]; For the award of this “badge of distinction” to Greene, see MacGunningle, Regimental Book, 98, 111. For Greene’s gravestone, see http://rihistoriccemeteries.org/newgravedetails.aspx?ID=146236 [accessed November 4, 2024].