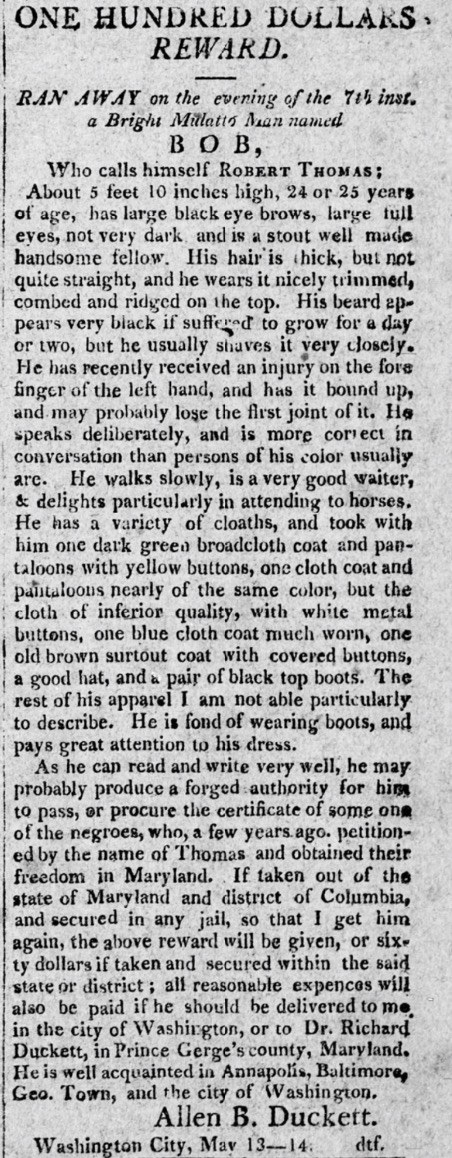

Between May 13th and July 19th, 1808, the National Intelligencer, the Independent American, the Alexandria Gazette, and the Aurora General Advertiser all posted daily advertisements that revealed details of the escape of Robert Thomas from “Washington City.” Robert Thomas, or “Bob,” was a mixed-race man, enslaved by Allen Bowie Duckett, a judge for the District Court of Columbia, who had been appointed by President Thomas Jefferson.[1] The Duckett family were long-established tobacco planters in Prince George’s county, Maryland.[2] Tobacco farming, an industry which depended upon enslaved labor, proved extremely lucrative for many Marylanders during the Revolutionary Era, including the Ducketts.[3] The Dr. Richard Duckett mentioned in the advertisement was Allen Duckett’s brother, who supervised some of these plantations.[4]

Judge Duckett lived in Prince George’s county for much of his life, and at the time of the 1800 Census, he lived there with four enslaved people.[5] It is possible that Robert Thomas was among them, as personal servants were often trained from a young age.[6] However, apparently Thomas was not “well acquainted” with the area, so it is just as likely that Duckett purchased him after moving to Washington D.C.

Robert Thomas worked as a personal servant to Duckett, a position which had a wide variety of duties. He would have been expected to complete physical tasks such as serving meals, preparing clothing, traveling with his enslavers, delivering messages, running errands, as well as performing other household chores.[7] Apparently Thomas also enjoyed caring for horses, suggesting a degree of skill and aptitude for working with these animals. Perhaps this is where he received the “injury” on his finger, revealing the dangers of enslavement, even as a personal servant.

However, Thomas’s work was not all physical, he knew how to “read and write very well.” While there were no anti-literacy laws in Maryland, teaching the enslaved to read and write was strongly discouraged, making these skills quite remarkable.[8] Thomas may have taught himself in secret, perhaps in a similar way to Frederick Douglass, who famously used the urban environment of Baltimore to teach himself to read and write.[9] However, he may have been taught to assist Judge Duckett with judicial tasks. Additionally, it is possible that through Duckett’s career, Thomas learned about methods to gain his freedom. There was a large library of books on Duckett’s estate, most of which were about law.[10] Thomas may have learned to read in secret when Duckett was away or in the late hours of the night and discovered legal methods to seek freedom. In particular, Thomas may have discovered the prospect of manumission, especially in Maryland, where the rates were quite high.[11] Perhaps Judge Duckett had denied Thomas’s request, convincing him to seek freedom by running away.

Robert Thomas’s literacy was likely tied to the opportunities he had as a mixed-race man. Mixed-race peoples sometimes had more specialized working conditions under slavery, including “house servants,” and as such received more training than those without recognizable white heritage.[12] Someone like Robert Thomas was more likely to receive these higher status positions because as visible members of their enslavers’ household, their appearance and demeanor reflected on their enslaver.[13] Thomas’s job as a “waiter” was one such publicly visible position. Judge Duckett described Thomas as “handsome,” deliberate, and capable: attributes that Duckett would have valued because they were a positive reflection on him.[14] This positive description suggests that Duckett had a begrudging respect for Thomas. Thomas’s escape further illustrates this tension between the enslaved and the enslaver; the more that Duckett trained Thomas to be a more presentable servant, the more tools and skills Thomas had to aid in his escape.

While Robert Thomas benefitted from certain privileges from his proximity to a wealthy family, his life in slavery remained unfree. The clothes that Thomas brought were likely ones that were given to him — the high-quality garments would be difficult for Thomas to obtain on his own — and were intended to represent Duckett, not Thomas, as wealthy and put-together.[15] While these clothes were an expectation placed on Thomas, he ultimately decided to escape with them. After all, they also portrayed Thomas as having the markers of a high-status man. Duckett’s advertisement noted that he was not able to describe the rest of Thomas’s clothing. This may indicate that Duckett was only listing the most expensive and luxurious items that Thomas took, and that he may have taken a more modest wardrobe as well, or perhaps Thomas simply amassed such a large collection of articles that Duckett was unable to recall them all.[16]

Advertisements in search of Robert Thomas ceased on July 19th, 1808. It is unclear if he successfully escaped or was captured. If Thomas was caught, he would not remain the property of Allen Duckett for long. Duckett died exactly one year after the posting of these advertisements on July 19, 1809.[17] If Thomas had been recaptured, he may have remained with the family, working for Duckett’s widow and child, as he would be familiar with their routines, or the Duckett’s may have bequeathed Thomas to somebody else.

However, Thomas very well may have been successful in his escape. It is likely that he was inspired by a successful Freedom Seeker before him, “Thomas,” as mentioned in the advertisement, and followed in his footsteps to obtain or forge a pass in Maryland. If so, he may have settled in Baltimore to embrace the anonymity of such a large population of free Black men — the largest in the state of Maryland (5,671 in 1810).[18] However, it is also likely that he sought freedom through the nearby port cities that he was familiar with, such as Annapolis or Baltimore, to settle in a northern city, like Philadelphia. What is clear about Robert Thomas — a respectable, literate man who had familiarity with the practice of waiting, equestrian work, and law — is that the skills he amassed through his enslavement did not just prepare him for a life of servitude, but also for a life of freedom.

View References

[1] “Important News,” Maryland Gazette, July 26, 1809.

[2] William G. Thomas, “Duckett Family Network,” O Say Can You See: Early Washington, D.C., Law & Family, https://earlywashingtondc.org/families/duckett [accessed November 25, 2025].

[3] Barbara Fields, Slavery and Freedom on the Middle Ground: Maryland during the Nineteenth Century (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985), 4.

[4] 1800 United States Census, Prince George’s, Maryland, digital image s.v. “Richard Duckett,” Ancestry.com [accessed November 1, 2025].

[5]1800 United States Census, Prince George’s, Maryland, digital image s.v. “Allen Duckett,” Ancestry.com, [accessed November 1, 2025]. It is unclear if these four enslaved people accompanied Duckett to Washington D.C., or if they remained in Prince George’s County.

[6] Erica Dunbar, Never Caught: The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge (37 Ink, 2018), 13.

[7] Dunbar, Never Caught, 29.

[8] Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave (1845) as re-printed in David W. Bright, ed., Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. 3rd Edition (Boston: Bedford, 2017), 64-69; While Douglass does not state any explicit anti-literacy laws, he does claim that “it is almost an unpardonable offense to teach slaves to read in this Christian country,” highlighting the de facto laws against literacy created by social stigma.

[9] Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, 64-69.

[10] “Notice,” National Intelligencer (Washington D.C.), September 18, 1809.

[11] Fields, Slavery and Freedom, 14-15.

[12] Robert Reece, “Genesis of U.S. Colorism and Skin Tone Stratification: Slavery, Freedom, and Mulatto-Black Occupational Inequality in the Late 19th Century,” The Review of Black Political Economy 45, (2018): 8.

[13] Dunbar, Never Caught, 28.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Laura F. Edwards, “Mr. Robinson’s Fabrics: Merchants,” in Only the Clothes on Her Back: Clothing and the Hidden History of Power in the Nineteenth-Century United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 2022), 61, 69; High-quality clothing would be difficult for Thomas to obtain because the materials were unaffordable, and merchants did not often sell to enslaved people.

[16] Edwards, Only the Clothes on Her Back, 61; Thomas may have obtained these articles through certain merchants who sold to enslaved people, produced them domestically, or made alterations to clothing that was given to him.

[17] “Important News,” Maryland Gazette, July 26, 1809.

[18] Fields, Slavery and Freedom, 62.