After dressing for the evening in her heeled shoes and red jacket, Sall slipped out of the house of her enslaver on Maiden Lane. “Well known in town,” the fourteen-year-old moved through the streets of New York recognizable and undeterred.[1] That night and the following evening when she disappeared again, Sall walked through paths adorned with names like King, Crown, and Queen, each referencing a monarch far, far away. Sall understood how her enslaver’s support kept her or perhaps led her to New York City when the British began their seven-year occupation of the city from 1776 to 1783.

During one of these nights in early March of 1783, Sall walked to a home close to the old barracks. There, she felt the pleasure of good company. She danced in her heels as her enslaver searched the neighborhood for her. Eventually, he’d learn of the joy she experienced that night dancing amongst friends. Spotting her, someone reported her presence to McCay. Yet Sall continued to outmaneuver him.

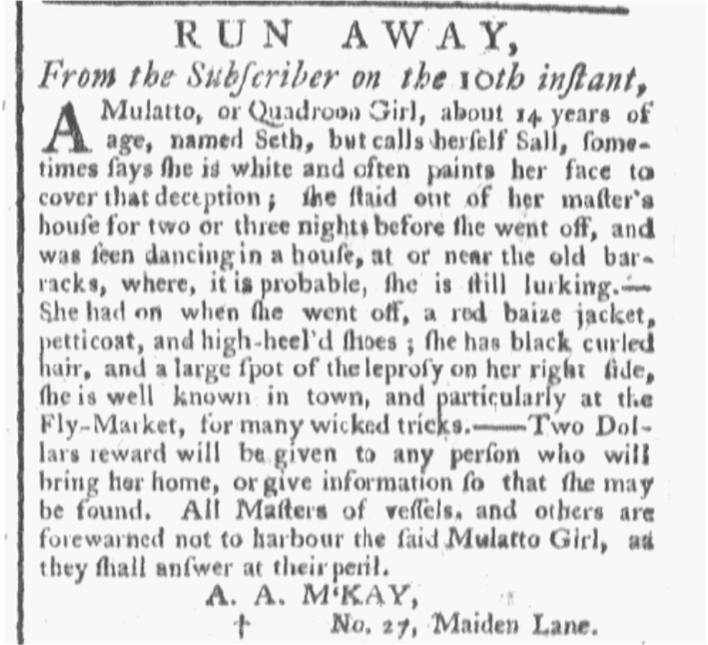

A few days later, on March tenth, Sall walked out of the Maiden Lane home once again. This time, however, Sall did not return after a night spent elsewhere. Her enslaver feared what might come next. Realizing she might outsmart ship captains, market goers, and anyone else she met, he visited James Rivington’s printing office and reported her missing. By the fifteenth of March, a runaway advertisement in the Royal Gazette featured the story he crafted of her escape five days earlier.

Circumventing her enslaver and his allies throughout New York, Sall charted a path through the streets of New York according to her own geographies.[2] She subverted white surveillance networks, “lurking” throughout town.[3] Sall formed relationships with people who protected her. She deceived those not invested in her safety, sometimes by “painting her face white.”[4] Her enslaver himself struggled to fit Sall into the hardening racial categorizations of the day, describing her simultaneously as “mulatto” and “quadroon.” Sall capitalized on these slippages, dancing between personas and white gazes to keep herself safe. She called herself Sall, rejecting her enslaver’s attempt to misname her Seth. Sall played “many wicked tricks” when she ventured down Maiden Lane towards the water to the popular Fly Market. There, she learned how to earn some money or trade goods for meat, produce, and fish. Deception paid. Near the wharf, time at the Fly Market undoubtedly introduced her to sailors and seamen whose ships docked in today’s East River. Her enslaver feared these connections and threatened punishment to maritime workers who “shall answer at their peril” if found guilty of helping Sall escape.[5]

Sall’s residence on Maiden Lane held significance not only for its proximity to the water. Nearly seventy-one years before fourteen-year-old Sall traversed the neighborhood, a group of at least twenty Africans set fire to an outhouse on the same street to signal the beginning of an armed struggle to end slavery. Met by local militias, the revolutionaries who participated that night risked their lives to overthrow the institution in New York.[6] Two generations later, survivors and their descendents passed down stories to children like Sall as another revolutionary struggle swept through the same streets. In Sall’s lifetime, whispers of freedom for men of African descent echoed throughout New York when leaders like Lord Dunmore or General Sir Henry Clinton promised manumission to those enslaved men who fought for the British cause.[7] Unable to enlist on either side of the cause, Sall took to her feet to seek liberation. Whether at the house near the barracks, in the marketplace, or wherever she may have left Maiden Lane for on March 10, 1783, Sall’s story demonstrates the ways that enslaved girls shaped and navigated the Revolutionary era.

In her “red baize jacket, petticoat, and high-heel’d shoes,” Sall dressed fashionably before she left the Maiden Lane home.[8] Her self-fashioning potentially reveals how Sall practiced freedom. It is emblematic of the long history of passing, especially for understanding how enslaved women and girls pursued freedom through dress. Nearly fifty years after Sall readied for that evening in March 1783, Harriet Jacobs escaped from her enslaver in North Carolina. The advertisement published to encourage her capture noted how Jacobs “a good seamstress… will probably appear, if abroad, tricked out in gay and fashionable finery.”[9] For Sall, her choice in dress perhaps allowed her to navigate the streets of New York as someone racialized as white. That, coupled with “painting her face white,” allowed Sall some protection as she navigated life as a young girl in New York.[10]

Beyond survival, the self-fashioning of enslaved girls and women reflected their rich and varied tastes as they adorned clothing and accessories that made them feel beautiful. Enslavers designed the institution of slavery to limit individual expression amongst the enslaved. Dress offers one window into understanding how enslaved girls like Sall chose to express themselves.[11] Maybe Sall cherished her heels. Maybe the redness of her jacket helped her feel lighter and happier in the colder and darker winter months as she skipped through the Fly Market surrounded by redcoats. As the War for Independence neared its end, the color red signaled an identification with the British rather than the revolutionaries. While we may not have exact answers, imagining the possibilities for Sall’s self-fashioning as she took back her days and nights in revolutionary New York offers windows into thinking about the worlds of enslaved girls and women during the revolutionary era.

View References

[1]As described by her enslaver in the newspaper advertisement. “RUN AWAY,” Royal Gazette, March 15, 1783.

[2] Stephanie Camp first posited that enslaved people created their own “rival geographies” that existed simultaneous to the geographies of containment built by enslavers. Stephanie Camp, Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004).

[3]“RUN AWAY,” Royal Gazette, March 15, 1783.

[4] For the long history of passing, see Allyson Hobbs, A Chosen Exile: A History of Racial Passing in American Life (Cambridge, Mass. and London: Harvard University Press, 2014).

[5] All the quotes in this paragraph are from “RUN AWAY,” Royal Gazette, March 15, 1783.

[6] Jill Lepore, New York Burning: Liberty, Slavery, and Conspiracy in Eighteenth-Century Manhattan (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005).

[7] Sylvia R. Frey, Water From The Rock: Black Resistance in a Revolutionary Age (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991); Julius S. Scott, The Common Wind: Afro-American Currents in the Age of the Haitian Revolution (London: Verso, 2018).

[8] “RUN AWAY,” Royal Gazette, March 15, 1783.

[9] “$100 Reward,” American Beacon, July 4, 1835.

[10] “RUN AWAY,” Royal Gazette, March 15, 1783.

[11] Jonathan Michael Square founded the digital project, “Fashioning the Self in Slavery and Freedom,” to highlight and interrogate how enslaved people related to fashion, both in their daily lives and through the development of the fashion industry. Fashioning the Self in Slavery and Freedom, https://www.fashioningtheself.com/ (accessed December 30, 2024). For an exploration of African American style from slavery through the 1940s, see Shane White and Graham White, Stylin’: African American Expressive Culture from Its Beginning to the Zoot Suit (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1998).