On the first Saturday of November 1793, Sarah broke from bondage, leaving fury rippling in her wake. Barely an adult, between eighteen and twenty years old, and already married and the mother of a nursing baby, she fled the largest island in the Chesapeake Bay.[1] Of average height, with a warm skin tone and short hair, Sarah vanished with two new linen patterns tucked away. Eight months later, an irate advertisement appeared in the pages of a Philadelphia newspaper.[2]

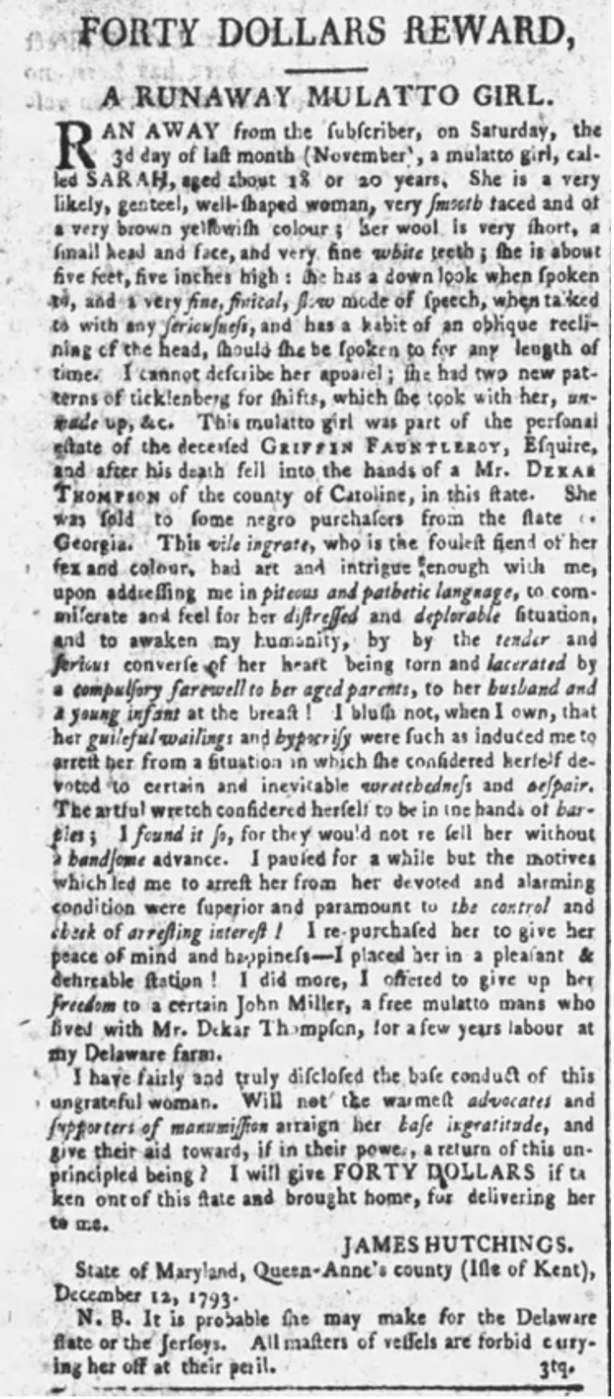

Runaway advertisements often seethe with anger, but few expose the emotional unraveling of an enslaver as vividly as James Hutchings’ notice for Sarah. Taking up nearly half a column in the Aurora General Advertiser and reprinted fourteen times during the summer of 1794, the advertisement exposes a man undone by an enslaved woman’s quiet ingenuity. Hutchings’ unrestrained prose—part confession, part tantrum—reveals how Sarah’s act of self-emancipation inverted the logic of slavery itself. Sarah was not the first enslaved person to escape Hutchings, but the preceding act of rebellion had prompted only a subdued reaction. Sarah’s actions sharpened the inversion: the enslaver could be outwitted, exposed, and unsettled by the very person he sought to own.[3]

Before her escape, Sarah had been born into bondage and likely never known freedom. She was enslaved by Griffin Fauntleroy, who had fought in the American Revolution before settling on a Maryland island off the Chesapeake and taking work as a coroner.[4] When he died in 1789, his Long Marsh Island plantation, Highfield, appeared in an estate sale notice compiled by local businessman and enslaver Dekar Thompson, listing objects and lives for purchase.[5] Sarah appeared among the “property,” recorded as one of the group of “fine” and healthy young people, cataloged for sale.[6] Her personhood was counted as an item listed between household furniture and “plantation utensils.”[7] Joining Sarah were several enslaved men and women, possibly including her parents.[8] This impending familial separation brought fear and anxiety to Sarah, as she searched for a way to avoid her seemingly inescapable fate.

In Thompson’s hands, Sarah’s fear came true: she, alone, was sold to Georgia slave traders. Facing a forced move, torn from her parents, husband, and baby, Sarah conceived a plan for survival. Around the time of her sale, she encountered James Hutchings, a ferry operator on Maryland’s Isle of Kent, seventy miles from her former home.[9] She saw an opportunity in him and seized it.

In his advertisement, Hutchings claimed that Sarah moved him with “piteous and pathetic language,” appealing to his compassion over the separation of her family. Hutchings apparently mistook her quiet demeanor—her “down look,” her “slow mode of speech,” and her habit of tilting her head—seeing only submission and obedience.[10] Sarah acted out the paternalistic fantasy Hutching needed to believe: that he was her savior, not her oppressor. He took the bait and painted himself as benevolent, offering her a “pleasant and desirable station.”[11] When enslaved women sought their freedom, enslavers frequently imagined their flight as temporary—an act of “truancy” or petit marronage rather than a claim to liberty.[12] Such forms of resistance were short-term absences where enslaved people withdrew their labor, visited kin, or sought a reprieve from violence.[13] Enslaved mothers, in particular, were assumed to return to their kinship networks and children, spouses, or parents left behind.[14] Hutchings’ decision to delay his advertisement after Sarah’s escape reveals confidence that she would return to bondage, reflecting the broader gendered pattern where enslavers mistook enslaved women’s flights for emotional ruptures rather than deliberate bids for freedom. When Sarah did not return, Hutchings’ humiliation hardened into fury.

After a terse discussion of the time and place of Sarah’s escape, Hutchings’ advertisement devolved into a public meltdown, unusual in its self-pity, sexualized observation, and emotional pleading. In eighteenth-century Maryland and Virginia, terms like “mulatto,” “yellow,” and “brown” marked both lineage and market value—signals of proximity to Whiteness and of the sexual exploitation that produced it.[15] Hutchings’ gaze sought to reduce Sarah into an object of obedience and desire, sublimating evidence of generations of violence. Hutchings interpreted Sarah’s escape not simply as the theft of property, but as an act of personal betrayal. The contradictions of slavery are laid bare in his language: he calls her both “the foulest fiend” and the recipient of his “humanity.”[16]

Sarah’s escape was an affront to Hutchings’ manhood.[17] He called her genuine fear “hypocrisy,” yet his elaborate defense of his own virtue only underscored how thoroughly she had exposed his weakness.[18] His insistence that he “repurchased her to give her peace of mind” masked a deeper wound: being outsmarted by someone he deemed incapable of reason.[19] Writing the notice became an attempt to reassert control—to rewrite the story in which Hutchings was not duped, but the wronged master. Yet his words preserve the opposite truth. Sarah had turned his system against him. In publishing the advertisement in Philadelphia, a city alive with free Black communities and anti-slavery presses, Hutchings publicly acknowledged his failure as an enslaver.[20] In the Aurora General Advertiser, Sarah forced him to confront what he could not imagine: turning an assertion of mastery into a printed confession of defeat.

By branding Sarah deceitful, Hutchings immortalized her self-emancipation, turning his humiliation into the very record that preserved her act. His fury shows how the escape of one young woman exposed slavery’s most fragile fiction: that mastery was absolute, and that “property” could not think, feel, or act with purpose. Sarah shattered this illusion, speaking with such clarity and force of emotion that she wounded Hutchings; what he read as deceit was simply her humanity—a fight to hold on to her family and herself. The same fear that threatened to destroy her became the strength that carried her toward freedom. Whether Sarah reached her family or continued north remains unknown. Yet, the agency she carved from nothing endures through the very words meant to condemn her.

View References

[1] Kent Island Heritage Society, “Kent Island History – Kent Island Heritage Society,” Kent Island Heritage Society, 2017–2025, https://kentislandheritagesociety.org/kent-island-history/ [Accessed October 2, 2025].

[2] After its initial appearance on July 11, James Hutchings ran the ad again on 14 separate occasions, inclusive of the issues on July 18, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 29, 30, 31, August 1, 2, 5, 6, and 14. “Forty Dollar Reward,” Aurora General Advertiser.

[3] “Advertisement.” Maryland Journal (Baltimore, Maryland), no. 488, January 7, 1783.

[4] Griffin Fauntleroy, Lt. Col. (5th Batt., Queen Anne’s County), September 4, 1777 in Maryland State Papers (Red Books), 1775–1827, MSA SSI 989 https://msa.maryland.gov/msa/stagser/s900/s989/html/ssi0989.html [accessed December 15, 2025]; “Commission issued to Griffin Fauntleroy appointed a Coroner in Queen Anne’s County in the room of Abner Turner deceased,” December 2, 1782, Journals and Correspondence of the Council of Maryland, 1781-1784 vol. 48, 312, Archives of Maryland Online, https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc2900/sc2908/000001/000048/html/am48–312.html [accessed December 15, 2025].

[5] “Advertisement,” Maryland Gazette (Annapolis, MD), (September 3, 1789); 1810 United States Census, Caroline, Maryland, digital image s.v. “Dekar Thompson,” Ancestry.com.

[6] “Advertisement,” Maryland Gazette, Sept. 3, 1789.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] “Advertisement,” Maryland Journal (Baltimore, MD), October 25, 1791); 1790 United States Census, Queen Annes, Maryland, digital image s.v. “James Hutchings,” Ancestry.com.; “Forty Dollar Reward,” Aurora General Advertiser.

[10] “Forty Dollar Reward,” Aurora General Advertiser.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Stephanie Camp, Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 39-40.; Amy Marie Johnson, “Slave Resistance in the Atlantic World,” Oxford Bibliographies in Atlantic History, last modified January 15, 2019, https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199730414/obo-9780199730414-0310.xml [accessed October 17, 2025].

[13] Deborah Gray White, Ar’n’t I A Woman? Female Slaves in the Plantation South (New York: Norton, 1985), 29.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Gretchen Neidhardt and Hope McCaffrey, “African American and Black Identity and Research Terms,” Chicago History Museum Research Center, August 20, 2021, https://libguides.chicagohistory.org/blog/African-American-and-Black-Identity-and-Research-Terms [accessed December 15, 2025]; Larry Hunt, “Mulattoes in Colonial Maryland: The Effects of Colonial Law on Patterns of Freedom and Enslavement,” Social Science Quarterly 103, no. 4 (July 2022): 945–58.

[16] “Forty Dollar Reward,” Aurora General Advertiser.

[17] Camp, 41-45.; David Doddington, “Manhood, Sex, and Power in Antebellum Slave Communities,” in Sexuality and Slavery: Reclaiming Intimate Histories in the Americas, ed. Catherine Clinton (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018), 145-158; Barbara Bush, “The Woman Slave and Slave Resistance,” in Slave Women In Caribbean Society, 1650-1838, ed. Barbara Bush (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990), 51-83.; Johnson, “Slave Resistance in the Atlantic World.”

[18] Forty Dollar Reward,” Aurora General Advertiser.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Nicole Penn, “George Washington’s Mount Vernon,” George Washington’s Mount Vernon, American Enterprise Institute, 2025, https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/aurora-general-advertiser [Accessed October 2, 2025]; Erica Armstrong Dunbar, “Voices from the Margins: The Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society 1833–1840,” in A Fragile Freedom: African American Women and Emancipation in the Antebellum City (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 70–95.