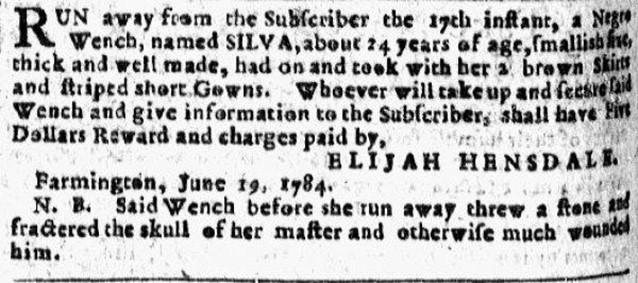

Silva’s story appeared in the Connecticut Courant on June 22, 1784. The Courant reprinted her story a week later, on the 29th, and once again on July 6th. Her story is one filled with violence, tragedy, and silence. For her story is also an account that reveals in explicit and implicit ways, the unusual complexities of everyday life suffered by many enslaved women before emancipation.[1]

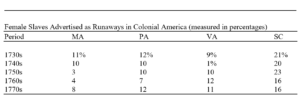

To start with, few enslaved women elected to run away. Over the course of the eighteenth-century, only a handful protested slavery with their feet. In New England, for example, female fugitives accounted for 7 per cent of those whose stole themselves. In the mid-Atlantic region of British North America, they made up approximately 10 per cent of the fugitive population. Even though the number of slaves in the eighteenth-century Chesapeake had been significantly larger than their counterparts in the North, women continued to represent a small part of fugitives in those full-blown slave societies. Up until 1780, 8 per cent absconded. In the Lowcountry, however, that had not been the case. In South Carolina, where slaves represented a Black majority, women accounted for on average 19 per cent of those who went away. In this setting, Silva’s story had been one of only a few.[2]

For most enslaved women in British North America, running away did not appear to be a viable option. Family ties probably discouraged women from taking flight. Some, for instance, did not leave because of deep and heart-felt connections they enjoyed to either their spouses or because of both the real and imagined kinships they had developed with other slaves. Most probably did not abscond because they also did not want to be separated from their children. Quite a few probably did not leave because of the precariousness of starting life anew. As a result, in different ways, they protested slavery. They resisted the peculiar institution. Silva, however, proved to be an exception to that rule.[3]

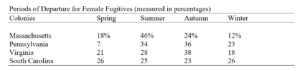

Like most freedom seekers in New England, she left when the weather got better. Determined to be her own master, she decided to flee during the warmer time of the year probably to escape the additional obstacle of the colder climes that characterized most New England winters. Not that different from her counterparts in the mid-Atlantic or in the southern colonies, she left during the summer. Anticipating a long sojourn, she carried with her additional clothing. With additional articles, she thought, she could pass for free. If not by dressing the part of a freedwoman, she could use them as a form of currency. Considering the warning to the public at large about aiding and abetting fugitives, she might have traded the additional items in an underground black market that must have existed not only in New England, but also in other colonies. Silva might have also had help in securing her freedom.[4]

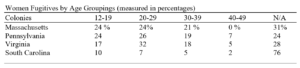

Like her fellow female fugitives in New England, she absconded young. In 1784, the fugitive, as her master made plain, left his place “about 24 Years of Age.” The ambiguous nature of his observation is not an unusual one. Quite the contrary, unless they had more direct knowledge on the matter, many masters guessed at the ages of their bondservants. Though it is impossible to know for certain how old fugitives were in exact terms, the extant accounts recorded in newspapers do provide us nonetheless some useful approximations. Most of the fugitive women in New England, for instance, left their owners either between their late teen years and their early twenties. Age probably engendered their brashness, time their imaginations, and, likewise, their dreams of freedom.[5]

In Silva’s case, her age might have played a role in her decision. Not long after the American Revolution, Connecticut passed a gradual abolition law that promised to free all children born into slavery after March 1, 1784, by the time they turned age 25. Slavery in the state would not end until 1848. Knowledge of this legislation might have represented yet another factor that encouraged Silva to leave. At the time of her flight, she was 24. One additional year a slave, she thought, might have been one year too long.[6]

Another reason explaining Silva’s flight might have been revealed in the postscript included in the advertisement for her apprehension. In what must have been a perilous environment, the young woman might have run away to escape sexual exploitation. To be sure, despite their pious past, their protestations that characterized race mixing as at once spurious and abominable, and even when confronted with the threat of corporal punishment, New Englanders proved themselves no less reprehensible than their neighbors in Pennsylvania, Virginia, South Carolina, or any other colony. Far from it, there, the horrifying implication of miscegenation appears to have been just as commonplace as elsewhere. Mulattoes or mixed-race people, for instance, represented almost 10 per cent of the fugitive population in New England. During the 1730s, four per cent of those who fled were described as such. On average, in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New Hampshire, almost one-tenth of the enslaved population overall were described as mulattoes. The brutal politics behind the meaning of the word miscegenation might indeed explain why Silva decided to run away. In other words, like other Black women who stole themselves away, she might have fled to escape the real possibility of being sexually molested.[7]

The postscript included in the advertisement printed for Silva’s capture also suggests that rape might certainly explain the violent details of her exit. Before she left Hensdale, the enslaved woman physically assaulted him. By the account of the incident reported in the newspaper, she had fractured his skull. The almost cavalier manner in which the incident had been recorded highlights not only the peculiar nature of slavery in America, but also the volatile nature that existed in most, if not all, relationships. between enslaver and enslaved. For if not rape, the enslaved woman might have had other, equally egregious, reasons for her actions. The selling of a child, for example, might have prompted the physical attack. The sale of a spouse or a loved one might also explain her actions toward the Farmington enslaver. Or her owner may have simply been a cold, callous man, one whose treatment warranted of his enslaved woman payback that came in the form of an intense altercation. Either way, Silva’s story reveals and conceals at once the precariousness of life most Black women confronted routinely during the eighteenth-century.

View References

[1] Connecticut Courant, June 29, 1784, 4; July 6, 1784, 1.

Based on the advertisements printed in the Connecticut Courant, the identity of the subscriber seems a bit unclear. At the time of publication, Silva wounded her master. Published three days after the assault, the advertisement is attributed to Elijah Hensdale. Hensdale, also spelled Hindale, was born on 1 April 1744 and died on 26 June 1797. His parents were John Hinsdale and Elisabeth (Cole) Hinsdale. Through his father, he learned the blacksmith’s trade. Not long after he married Ruth Bidwell, he began to amass an estate that included a farm and a mulberry orchard. In addition to blacksmith and farming work, he worked in the silk industry. If he was Silva’s master at the time of flight, and the postscript included in the notice had simply been the work of the printer, the assault did not prove fatal as Hinsdale would die over a decade later. But if Elijah was not the subscriber at the time of the assault, it is also plausible that Connecticut native might have been acting on the behalf of a family member, perhaps one of his male siblings, if not his father, who might have owned the fugitive woman. According to Camp’s History of New Britain, Elijah Hinsdale had three brothers: John Hinsdale who died young, how young is unknown; Theodore Hinsdale (25 November 1738-29 December 1818); and John Hinsdale (21 August 1749-????). Elijah’s father, John, was born 13 August 1706 and died 2 December 1792 at age eighty-six. At any rate, more so than anything else, the postscript included is the most striking aspect of the advertisement that appeared in the Connecticut Courant. David Nelson Camp, History of New Britian: With Sketches of Farmington and Berlin, Connecticut, 1640-1889 (New Britian: William B. Thomson & Company, 1889), 397-398; 431.

[2] Without question, running away was a form of slave resistance that was gender specific. Even though the institution of slavery varied over time and space, men protested with their feet in comparably higher numbers.

Sources: Lathan A. Windley, Runaway Slave Advertisements: A Documentary History. New York: Greenwood Press, 1983. 4 vols; Billy G. Smith and Richard Wojtowicz, Blacks Who Stole Themselves: Advertisement for Runaways in the Pennsylvania Gazette, 1728–1790. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989; Graham Russell Hodges and Alan Edward Brown, ‘Pretends to Be Free’: Runaway Slave Advertisements from Colonial and Revolutionary New York and New Jersey. New York: Fordham University, 1994; Antonio T. Bly, Escaping Bondage: A Documentary History of Runaway Slaves in Eighteenth-Century New England, 1700–1789. Maryland: Lexington Books, 2012; Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers Database; and, Eighteenth-Century American Newspapers in the Library of Congress in Microfilm.

[3] Billy G. Smith, ‘Black Women Who Stole Themselves in Eighteenth-century America’, in Inequality in Early America, ed. Carla Gardina Pestana and Sharon V. Salinger (Hanover and London: University Press of America, 1999), 134–59.

[4] Like their male counterparts, women absconded when the weather got better. Overwhelming, enslaved African American women preferred the summer months as well, that more than likely reflected a change in work cycles.

Sources: Lathan A. Windley, Runaway Slave Advertisements: A Documentary History. New York: Greenwood Press, 1983. 4 vols; Billy G. Smith and Richard Wojtowicz, Blacks Who Stole Themselves: Advertisement for Runaways in the Pennsylvania Gazette, 1728–1790. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989; Graham Russell Hodges and Alan Edward Brown, ‘Pretends to Be Free’: Runaway Slave Advertisements from Colonial and Revolutionary New York and New Jersey. New York: Fordham University, 1994; Antonio T. Bly, Escaping Bondage: A Documentary History of Runaway Slaves in Eighteenth-Century New England, 1700–1789. Maryland: Lexington Books, 2012; Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers Database; and, Eighteenth-Century American Newspapers in the Library of Congress in Microfilm.

[5] Much in the same way that weather played a role in slaves’ plans to steal away, the same is true with regards to age. Throughout British America, between twenty and twenty-nine represented the most likely age cohort for fugitive women.

Sources: Lathan A. Wndley, Runaway Slave Advertisements: A Documentary History. New York: Greenwood Press, 1983. 4 vols; Billy G. Smith and Richard Wojtowicz, Blacks Who Stole Themselves: Advertisement for Runaways in the Pennsylvania Gazette, 1728–1790. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989; Graham Russell Hodges and Alan Edward Brown, ‘Pretends to Be Free’: Runaway Slave Advertisements from Colonial and Revolutionary New York and New Jersey. New York: Fordham University, 1994; Antonio T. Bly, Escaping Bondage: A Documentary History of Runaway Slaves in Eighteenth-Century New England, 1700–1789. Maryland: Lexington Books, 2012; Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers Database; and, Eighteenth-Century American Newspapers in the Library of Congress in Microfilm.

[6] Bernard C. Steiner, The History of Slavery in Connecticut (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1893), 28-29.

[7] The Acts and Resolves, Public and Private, of the Province of the Massachusetts Bay (1692–1714; Boston, 1869), 1:52 [fornication], 578; Acts and Resolves . . . of the Province of the Massachusetts Bay, 1:698. Lorenzo J. Greene, The Negro in Colonial New England (New York: Atheneum, 1974), 203-209. References to enslaved African American’s racial background conceal a tragic story in which people of African descent confronted sexual violence. Though it varied over time and space, miscegenation was a fact of life in British North America. While some relationships between blacks and whites may have been consensual, most probably were not. Instead, in many instances, they were complicated interactions in which blacks and whites fought one another in a variety of ways.