The revolutionary acts of those who sought to end their own enslavement did not always align with or take inspiration from American revolutionary ideology. Freedom seekers may have taken advantage of the chaos of the revolutionary era while acting independently of it. Such was the case of Solomon, who was as driven by a determination to live as free as Patrick Henry or Thomas Jefferson, even if he was not necessarily inspired by the rhetoric about liberty. Born and raised in Africa, Solomon had been in North America only a couple of years when his relentless drive to be free began.

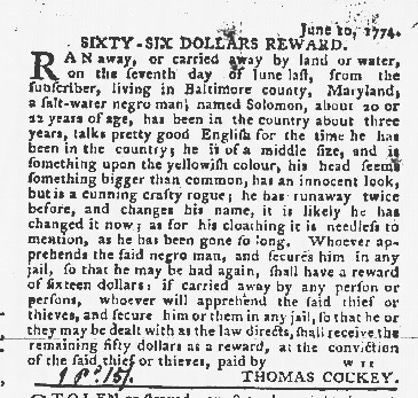

Solomon first escaped soon after his arrival in Maryland. When Thomas Cockey advertised for the freedom seeker in June 1774, Solomon had been free for about a year. Only about three years out of Africa, this was already Solomon’s third escape attempt and was likely his most successful to date. Little wonder that Cockey described the young man as “a cunning crafty rogue” who belied his “innocent look.” In his early twenties, Solomon was “a salt-water” man, meaning that he worked aboard ocean-going ships operating out of Baltimore. Of a middling size with a large head, he spoke “pretty good English” considering his short time in the Americas.[1]

We do not know how, when, or where Solomon was recaptured, but we do know that his enslaver took precautions to make sure the young man did not escape again, having an iron collar fitted around Solomon’s neck, fetters around his ankles, and a chain attached to one of these fetters. These restraints failed, for in May of 1775 Solomon escaped for a fourth time. On this occasion he eloped with a White servant man named Richard Dawson, a fifty-five year-old English convict who had been exiled by English courts and his labor sold to Cockey as part of his punishment. Cockey believed the two men would “make for Boston to the [British] soldiers, as they have often been talking about them.” Dawson also had an iron collar around his neck, and Cockey thought it “likely they may get their irons off, get other cloaths, change their names, and deny their master, as the negro has always done.” For Solomon, at least, Loyalism may have meant little other than an opportunity to join the King’s forces as a free man, rather than a commitment to a particular cause.[2]

Perhaps what is most interesting about this advertisement is the information it contained about Solomon’s previous (third) escape. On that occasion the young man had made his way to New Castle in Delaware, where he had resided for a year or longer, spending at least some time in nearby Philadelphia. In July 1774, Solomon had made his way to Somerset County, Maryland, after which he had been taken up and imprisoned; in November 1774 Cockey had reclaimed the freedom seeker and brought him back to Maryland. Following Solomon’s fourth escape, the advertisement for him was reprinted at least six times (between May 16 and September 18, 1775) in both Maryland and Philadelphia newspapers. On October 5th, Solomon was taken into custody by Ralph Foster in Prince George County, Maryland. Foster advertised that he had possession of “a Negro Man, who says his name is Solmon, and that he belongs to Thomas Cockey,” and that the enslaver could reclaim him upon payment of charges.[3]

But this would not be Solomon’s last escape, nor would it mark the end of his adventures in freedom. In the fall of 1776 he escaped for a fifth time, and he remained free for at least two years. When another enslaved man named Tooley escaped from Cockey in late September of 1778, the enslaver advertised for Tooley in the Maryland Journal but also described Solomon who had been absent for two years. Cockey reiterated that during a prior escape Solomon had been in New Castle and Philadelphia, and then incarcerated in the Somerset county jail, and once again, the man who would be free was described by Cockey as having “an innocent look, but is a great rogue.”[4]

Solomon was again recaptured, which we know because two years later on March 11, 1780, Solomon escaped from Cockey for at least the sixth time despite the fact that he had again been fitted with an iron collar around his neck. On this occasion Cockey made Solomon’s African identity clear, describing him as “a Guinea Negro Man,” and wearily the enslaver reiterated that despite his “harmless look” Solomon was “a sly villain.” Noting that Solomon would have endeavored to have the iron collar removed, Cockey informed readers that Solomon would “change his name, as he has done before, and his cloaths, as soon as possible, as he is fond of dressing.” Clearly the young man took pride in his appearance, and Cockey made note of Solomon’s hair in pejorative terms, stating that his “wool is longer than common, which he commonly keeps dressed.” Having previously escaped with a White servant, on this occasion Solomon was partnered with Eben, another “Guinea Negro Man” who had escaped from Cockey. Perhaps most interesting was the enslaver’s revelation that during his previous lengthy period of liberty Solomon had “been at Fort Pitt, and many other places about the country, and ‘tis likely [he] will endeavour to pass for a free man.”[5]

Fort Pitt was an American base for defensive operations against violent resistance by the Indigenous allies of the British. Daniel Brodhead organized several operations along the Allegheny River, occasionally engaging with Seneca and other Indigenous warriors, and sacking and burning empty Indigenous settlements. Did Solomon take part in these or related operations? What else might he have done during his long periods of freedom when he had made his way to “many other places about the country”? We cannot know. But what we do know is that Solomon’s determination to be free had little to do with American Patriots’ contemporaneous struggles for individual and national liberty. He appears to have taken advantage of the chaos of these years, and the needs of Patriot and perhaps even British commanders for young and able fighting men, or for manual or skilled workers such as seafarers. Not even the fitting of shackles, chains, and collars held Solomon back, and twice he escaped while wearing these highly visible markers of enslaved status, contriving to have them removed and to remain at liberty.[6]

There appear to be no other mentions of Solomon in surviving records, although of course he may appear under another name or names. The American Revolution was not necessarily so much a causal factor as a backdrop for this determined young African man to repeatedly try to free himself. Had he been recaptured and returned to Cockey it seems likely that such a determined freedom seeker would have escaped again. Perhaps this final bid for freedom was successful.

View References

[1] “SIXTY-SIX DOLLARS REWARD… Solomon,” The Maryland Gazette (Annapolis), June 23, 1774. This advertisement indicated that Solomon had escape in June of the previous year, and that he had escaped twice before this.

[2] “THIRTY POUNDS REWARD… RICHARD DAWSON… SOLOMON,” Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette; Or The Baltimore General Advertiser (Baltimore), May 16, 1775. For more on this advertisement see Carl Robert Keyes, “July 4, 2025,” The Adverts 250 Project: An Exploration of Advertising During the Era of the American Revolution, 250 Years Ago This Week,’ https://adverts250project.org/tag/thomas-cockey-sr/ [accessed November 7, 2025].

[3] “THIRTY POUNDS REWARD… RICHARD DAWSON… SOLOMON,” Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet. Or, The General Advertiser (Philadelphia), May 22, June 26, July 10, August 14, September 4, September 18, 1775; “Prince George’s County, Nov. 5, 1775. COMMITTED to my Custody… Solomon,” Maryland Journal (Baltimore), November 22, December 5,1775.

[4] “TWO HUNDRED DOLLARS REWARD… SOLOMON… TOOLEY,” Maryland Journal (Baltimore) October 13, 1778.

[5] “NINE HUNDRED POUNDS REWARD… BOATSWAIN… EBEN… SOLOMON,” The Maryland Journal, and Baltimore Advertiser (Baltimore), March 21, 1780.

[6] “Fort Pitt During the Revolutionary War: General Brodhead’s Expedition,” Heinz History Center Blog, https://www.heinzhistorycenter.org/blog/fort-pitt-museum-fort-pitt-during-the-revolutionary-war-general-brodheads-expedition/ [accessed November 7, 2025].