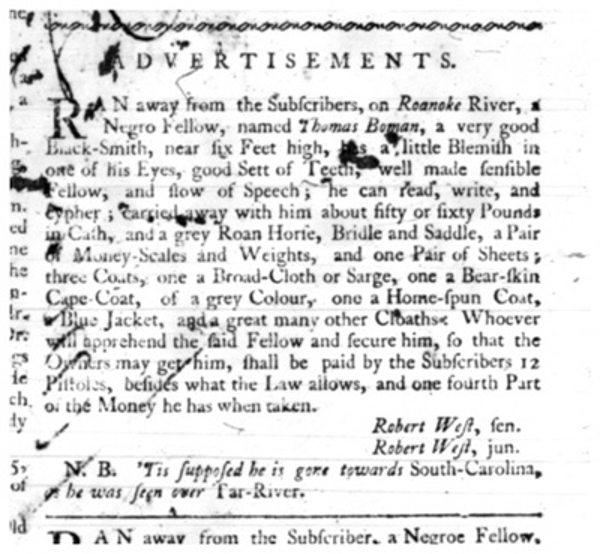

On March 13th, 1752, enslavers Robert West Junior and Senior placed an advertisement in the North Carolina Gazette seeking a man named Thomas Boman.[1] Born around 1730, Thomas Boman was an educated and skilled enslaved man living in North Carolina, likely on or near the coast and New Bern where the advertisement was published.[2] The advertisement does not reveal exactly where Boman was enslaved. He was surely familiar, however, with North Carolina’s coastal plains, an eastern region of the state, developing as an agricultural area with webs rivers, swamps, and emerging port cities. It is in the context of the distinctive region of North Carolina and his skilled labor that we can understand the unique life and resilience of Thomas Boman.

For Boman to flee to the Roanoke River was a strategic decision, giving him access to a known escape route. The Roanoke River covers a great distance, running from West Virginia to Eastern North Carolina. Additonally, the Tar River runs from Northern North Carolina and ends in Eastern North Carolina. Both rivers empty into a coastal estuary, the Albemarle-Pamlico, leading to the Atlantic Ocean. Because of this unique geography, the rivers and coastline created great appeal and opportunity for freedom seekers, featuring remote swamps and dense forests as safe havens, both short and long term.[3] We cannot be entirely sure of Boman’s intended plan, but he may well have made for the coast, which was accessable via both the Roanoke and Tar rivers, and would have offered multiple options for some level of autonomy.

Perhaps along this journey, Boman may have relied on the benevolence of small communities of Maroon people, as a modest, but growing number of North Carolinian freedom seekers did at this time.[4] Boman’s escape differed from that of freedom seekers in other colonies, as North Carolina and Virginia were home to the largest and perhaps the only maroon communities north of Georgia and Florida.[5] Maroons were enslaved people who had escaped and then established lives for themselves in the wilderness, living largely in secret and without any form of direct control from outsiders.[6] Self determination was the objective. Particularly in Virginia’s Great Dismal Swamp, their ability to create societal structures eventually became so successful that Maroons were able to hire themselves out to White employers, faking free papers.[7] For Thomas Boman, a community like this, where he could keep whatever he was able to earn, would surely have been appealing to him as a skilled laborer. Beyond practical matters of employment, this would have cultivated a new sense of potential and community, and the promise of a newfound level of autonomy. Regardless of his intention, Boman’s distinctive position as a North Carolinian freedom seeker and his skilled labor, as well as the money and property he carried with him, may have granted him access to the maroons, which would’ve aided his freedom.

Beyond his regional advantages, Thomas Boman’s skilled labor would have given him special abilities to seek freedom. In the advertisement placed by the Wests, the enslavers described him as “a very good Black-Smith” who was able to “…read, write and cypher.”[8] Boman’s labor skills were uncommon as scholars have estimated that only eleven percent of freedom seekers in North Carolina at this time were skilled artisans.[9] The ability to read and write was even more unusual, although it was likely entwined with his status as an artisan. Skilled craftsmen like Boman often were hired out or allowed to travel and secure work by themselves, moving from place to place, and then paying his enslavers most of what he had earned. Working like this would have given Boman an advantage in learning local geography, as well as broadening his experience of interacting with White people.[10] This itinerant status sometimes allowed enslaved artisans to “pass” as freed black men.[11] We cannot be sure of where he had learned his skills, but blacksmithing was highly developed in Africa by the late 15th century. It is more likely, however, that he had been trained on the plantation, given that the advertisement did not identify him as having been born in Africa.[12] Enslaved and freed blacksmiths at this time were vital to the development of the early American economy, both rural and urban.[13] Additionally, blacksmiths may have played a unique role in organizing slave rebellions, being able to rescue bondspeople who escaped slavery wearing collars and chains, as well as produce weapons to defend themselves.[14] Thus these experts used iron to resist oppression and perhaps to preserve African traditions. It is in this that we can gain a greater understanding of Thomas Boman’s skills and contribution to his community’s cultural resilience–and his own resistance in seeking freedom.

Given his considerable skills, his enslavers unsurprisingly offered a significant reward for his capture. The Wests offered a reward of “12 Pistoles.” Pistoles, or Doubloons, were Spanish coins circulating the American market during the mid 1700s, as colonists could not mint their own currency.[15] Their willingness to part with hard silver or gold currency to secure his return underscores his value. The financial loss Bowman’s escape represented was no doubt accentuated by the numerous possessions Boman took with him. The Wests describe him as carrying: fifty to sixty pounds in cash, a grey Roan horse, bridle and saddle, a pair of money scales and weights, one pair of sheets, three coats, a bear skin coat, a home spun coat, a blue jacket, and many other clothes.[16] There are multiple notable items in this list. The cash, which the Wests claim was stolen, was a very large sum. Additionally the number of items listed would have required a significant amount of effort to carry on this journey: he could not have taken so much had he not also stolen a horse.

Perhaps the most significant aspect of Boman’s journey to freedom is the distinct possibility that he succeeded. Nineteen years later, in 1771, a Thomas Boman was listed as a “free Molatto” in John Moore’s household in the Bertie County tax list. This was corroborated in tax lists from 1772 and 1774.[17] We cannot be certain that this was the same man: the West’s advertisement identified him as “negro” while these later records referred to a “mulatto” man. The term “Mulatto” refers to someone who is mixed race, whereas “Negro” usually described a person of African descent. It is, however, a sufficiently unusual name to make it very possible, and perhaps even likely, that this was the man who had escaped from the Wests, and who now lived as a free man. If this was the same man, we do not know exactly how his escape played out, and how or where he had lived over the preceding two decades. We do know, however, that such a man had displayed great bravery to not only escape and survive but to make a livelihood again. Thomas Boman risked everything to be free–and on some level–he may well have succeeded.

View References

[1] “RAN away… Thomas Boman,” North Carolina Gazette (New Bern, NC), March 13, 1752. This advertisement has been re-printed in Alan D. Watson, ed., African Americans in Early North Carolina: A Documentary History (Raleigh: North Carolina Office of Archives and History, 2005), 56-57.

[2] Paul Heinegg, Free African Americans of North Carolina, Virginia and South Carolina: From the Colonial Period to About 1820., vol. 1 (Baltimore, Maryland: Clearfield, 2001) 145.

[3] David S. Cecelski, “The Shores of Freedom: The Maritime Underground Railroad in North Carolina, 1800-1861,” The North Carolina Historical Review 71, no. 2, (1994), 177–178.

[4] Marvin Kay, “Slave Runaways in Colonial North Carolina, 1748-1775,” The North Carolina Historical Review 63, no. 1, (1986) 4–5.

[5] Sylviane Diouf, Slavery’s Exiles: The Story of the American Maroons, (New York, NY: New York University Press, 2014), 210.

[6] Diouf, Slavery’s Exiles, 1.

[7] Diouf, Slavery’s Exiles, 213.

[8] “RAN away… Thomas Boman,” North Carolina Gazette (New Bern, NC), March 13, 1752.

[9] Marvin Kay, Slavery in North Carolina, 1748-1775, (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 259.

[10] Kay, Slavery in North Carolina, 130.

[11] Kay, Slavery in North Carolina, 131.

[12] Ana Lucia Araujo, “The Power of Art: The World Enslaved Blacksmiths Made in the Americas” (presentation, CSAAD Africa-Diaspora Forum Series 2024-2025 at NYU, New York, NY, April 1, 2025) 7:17-7:25.

[13] Araujo, “The Power of Art…” 23:44-24:08.

[14] Araujo, “The Power of Art…” 25:50-27:25.

[15] John J. McCusker, Money and Exchange in Europe and America, 1600-1775: A Handbook. (Chapel Hill, N.C.: The University of North Carolina Press, 1978), 13.

[16] “RAN away… Thomas Boman,” North Carolina Gazette (New Bern, NC), March 13, 1752.

[17] Paul Heinegg, Free African Americans of North Carolina, Virginia and South Carolina: From the Colonial Period to About 1820., vol. 1 (Baltimore, Maryland: Clearfield, 2001) 145.