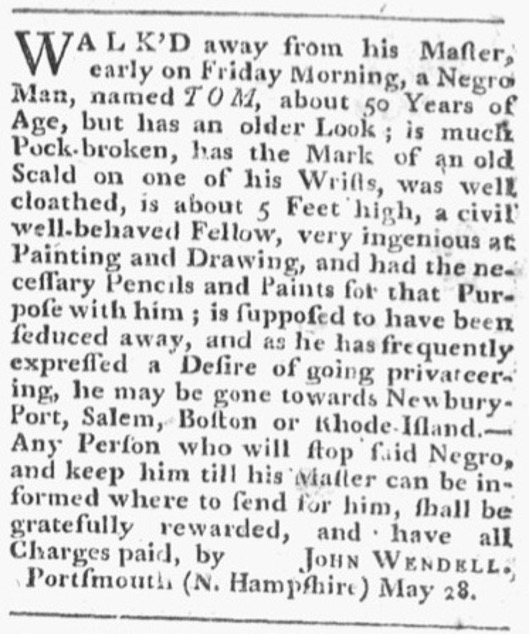

Tom was already about fifty years old when he made his bid for freedom. The War for Independence was drawing towards a close, as British forces withdrew from the Carolinas into Virginia, and were defeated at Yorktown a few months later. Slavery had been weakened throughout the new United States, particularly in New England, and more and more of the region’s enslaved people were actively challenging their bondage. We do not know whether Tom was from Africa, or it he had been born close by or elsewhere in the Americas. The advertisement makes no mention of his ability to communicate in English, suggesting that he had spent most or even all of his life among English-speakers, and this was likely either his only language or the one with which he was most familiar.

He was well-dressed, as befitted the enslaved servant of John Wendell, a leading Patriot in Portsmouth, a Harvard graduate, and a successful lawyer and property-owner.[1] Tom’s face had been scarred by smallpox, and Wendell indicated that Tom looked older than his fifty-odd years. Wendell warned readers that Tom had “frequently expressed a Desire of going privateering,” joining the crew of one of the ships that sailed from New England ports to prey on British ships sailing between North America, the Caribbean, and the British Isles. Even a small share of captured ships and cargoes might give Tom more money than he had ever seen. But at fifty he would have been very old for seafaring: one study of New England sailors in the years before the War for Independence found that most had left the sea by the age of 30, while very few worked before the mast after reaching forty, and none were older than that.[2]

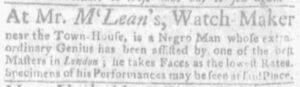

If Tom had made it to a port, it seems likely that his age would have made joining a privateer difficult if not impossible. When Wendell described Tom’s skill as an artist, he was indicating what was a more likely means of survival for the older man. There are certainly records of free and enslaved men who made money, and even a living, through their artistic skill, including this advertisement from a Boston newspaper in 1773.

Operating out a watchmaker’s shop, this unnamed Black man showed examples of his sketches of customers and then undertook new assignments on commission.

A better-known example is Scipio Moorhead, who was taught to draw and paint by Sarah, the wife of his enslaver the Reverend John Moorhead of Boston, and who painted and sold portraits in pre-revolutionary Boston. No works survive bearing his signature, but the engraving of an image of Phillis Wheatley that appeared in her 1773 collection of poems was quite likely based on a drawing by Moorhead.[3] Wheatley appears to have been impressed by Moorhead’s skill, for she eulogized him in her poem included in her 1773 volume, entitled “To S.M., A Young African Painter, On Seeing His Works.”

To show the lab’ring bosom’s deep intent,

And thought in living characters to paint,

When first thy pencil did these beauties give,

And breathing figures learnt from thee to live,

How did those prospects give my soul delight,

A new creation rushing on my sight?…

Still may the painter’s and the poet’s fire

To aid thy pencil, and thy verse conspire![4]

Wheatley interpreted Moorhead’s paintings from the perspective of her own artistic creativity, and her appreciation of the skill of this “wond’rous youth” is a moving tribute to a fellow Black New Englander. Wheatley was all too aware that their abilities, and her articulation of them, implicitly challenged the very foundations of their former enslavement.[5]

The Boston Evening-Post (Boston), August

20, 1770.

Pompey Fleet was another enslaved man in New England with artistic ability. Trained as a printer and woodcut artist in the Boston workshop of Thomas Fleet, Pompey Fleet escaped in 1774. He joined the British forces and worked as a printer in New York, eventually voyaging on to Nova Scotia and then Sierra Leone, where he established the first printing press in West Africa. First in New England and then in these other location, Pompey Fleet drew and then carved the simple, stylized images that created the woodcut images appearing in the newspapers, pamphlets, and books that he printed. The examples below feature woodcuts printed by the Fleet family, which were quite likely crafted by Pompey Fleet. While these images appear to the modern eye somewhat crude and simple, they require considerable skill to produce: the printer Isaiah Thomas regarded Fleet as one of New England’s most skilled woodcut artists.[6]

Was Tom able to make his way to freedom, and perhaps make a living for himself through his art? In 1790, nine years after he eloped, the first federal census recorded that John Wendell was head of a household of nine people, including himself, three females, four male children, and one enslaved person. Was this Tom? Perhaps Tom had returned or been recaptured. According to the 1790 census there were 157 enslaved people in New Hampshire and 640 free people of color. A decade later the second census revealed that the state’s enslaved population had shrunk to 8, while there were now 852 free people.[7] But Tom had already been about fifty years old when he had eloped in 1781: he would have been around sixty by the time of the first census, which was roughly the life expectancy for adult White males in coastal New England at this time. By 1800 he would have been around 70, and if alive he was a very old man.[8]

Whether free or enslaved, what did his art mean to Tom? Is it possible that in sketching and painting he found a freedom he did not enjoy in life? At the very least it may have been a skill that was his, separate from the labor required of him by Wendell, something that could not be owned and controlled by others.

View References

[1] “Wendell, John, 1731-1808,” Person Record, Portsmouth Athanæum, https://athenaeum.pastperfectonline.com/byperson?keyword=Wendell%2C%20John%2C%201731-1808 [accessed November 21, 2024]. Wendell’s property transactions and sale of land and buildings appeared regularly in the press: see, for example, “A Convenient well finished DWELLING HOUSE… to be sold,” New-Hampshire Gazette State Journal June 18, 1781, and “The Subscriber having a large number of Lots of Land in well settled Towns in this State…,” New-Hampshire Gazette State Journal September 29, 1781.

[2] Daniel Vickers and Vince Walsh, “Young Men and the Sea: The Sociology of Seafaring in Eighteenth-Century Salem, Massachusetts,” Social History, 24 (1999), 26-8.

[3] “Scipio Moorhead,” (2011), Benezit Dictionary of Artists, Oxford Art Online, https://www.oxfordartonline.com/benezit/display/10.1093/benz/9780199773787.001.0001/acref-9780199773787-e-00204425?rskey=eNWq6E&result=3 [accessed November 21, 2024].

[4] Phillis Wheatley, “To S.M. a young African Painter, on seeing his works,” in Poems On Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. By Phillis Wheatley, Negro Servant to Mr. John Wheatley, of Bostin, In New England (London: for A. Bell, 1773), 114-5.

[5] For more on Wheatley’s poem, and on Moorhead and their relationship, see David Waldstreicher, The Odyssey of Phyllis Wheatley: A Poet’s Journeys Through American Slavery and Independence (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023), 185-6, 27, 54, 184.

[6] Isaiah Thomas, Three Autobiographical Fragments (Worcester: American Antiquarian Society, 1962), 31. For more information see Gloria Whiting, “Pompey Fleet (June 1774),” Freedom Seekers: Stories of Black Liberation in the American Revolutionary Era and Beyond, https://freedom-seekers.org/story/pompey/ [accessed November 21, 2024].

[7] Entry for John Wendell, Portsmouth Town, Rockingham County, Heads of Families At the First Census of the United States in the Year 1790. New Hampshire (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1907), 81; Negro Population, 1790-1915 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1918), 57. See also Dinah Mayo-Bobee, “Servile Discontents: Slavery and Resistance in Colonial New Hampshire, 1645-1785,” Slavery and Abolition, 30 (2009), 339-60.

[8] Entry for John Wendell, Portsmouth Town, Rockingham County, Heads of Families At the First Census of the United States in the Year 1790. New Hampshire (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1907), 81; Negro Population, 1790-1915 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1918), 57. See also Dinah Mayo-Bobee, “Servile Discontents: Slavery and Resistance in Colonial New Hampshire, 1645-1785,” Slavery and Abolition, 30 (2009), 339-60. For life expectancy, see Stephen J. Kunitz, “Mortality Change in America, 1620-1920,” Human Biology 56 (1984), 559-82.