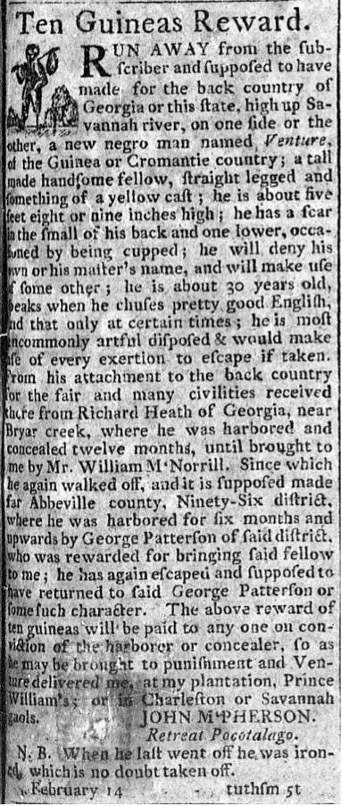

Venture first entered the historical record in February 1792, when the City Gazette of Charleston, South Carolina posted an advertisement offering ten guineas for his capture. The notice described him as “a tall made handsome fellow, straight legged, something of a yellow cast,” about thirty years old, with cupping scars on his back. He spoke “pretty good English,” though “only when he chuses.” His enslaver, John McPherson, labeled him as “artful[ly] disposed,” intending insult but inadvertently revealing Venture’s skill at reading situations, choosing words strategically, and seizing opportunities to resist.[1]

Venture was born in West Africa, in the “Guinea or Cromantie country,” a region known to Europeans as the Gold Coast. This region was dominated by the kingdom of Asante, composed of Akan-speaking groups that made up the largest segment of the region’s population in the eighteenth century.[2] Despite their diversity and lack of a shared identity, Europeans lumped Africans from the Gold Coast together as the so-called “Coromantee nation.”[3] The term, now understood as outdated and offensive, came from the English fort at Cormantyn (Kormantine) and was used by Europeans to categorize, stereotype, and control Africans in the Atlantic world, often associating the so-called “Coromantee nation” with strength, capability, and resistance.[4] Its appearance in colonial records reveals how ethnic designations became tools for racialization and for projecting fears of resistance onto enslaved Africans.

After surviving capture and the Middle Passage, Venture was sold to McPherson, a planter at Retreat Plantation near Pocotaligo in Prince William’s Parish, South Carolina.[5] The parish was part of the Anglican establishment that structured South Carolina’s civic life: vestries managed infrastructure, education, welfare, and taxation.[6] McPherson, a substantial landowner, was deeply embedded in the colony’s political networks. He served in the General Assembly in the 1780s, sat in the State Senate from 1792 to 1805, and was a delegate to the 1788 state convention that ratified the federal Constitution.[7] Through distant family ties, he was even connected to President George Washington.[8]For men like McPherson, these institutions secured power and legitimacy; for enslaved people like Venture, they defined the boundaries of a world he repeatedly tried to escape.

The American Revolution produced upheaval across the Atlantic world. While white colonists fought for independence, enslaved people used the chaos to pursue their own liberation—fleeing plantations, reshaping labor conditions, and sometimes joining British forces. Revolutionary rhetoric challenged assumptions about race and servitude, destabilizing hierarchies in the southern states.[9] Life at Retreat Plantation, like on many estates, would have been grueling: enslaved people labored in sweltering, mosquito-filled swamps where disease was rampant and discipline was enforced through violence. Planters skimped on food, clothing, shelter, and medical care, making plantations among the deadliest in mainland North America.[10] Venture’s repeated escapes reveal not only a desire to avoid physical suffering but also a determination to reclaim autonomy amid severe danger.

His flight unfolded during a transitional period in Lowcountry history. The “plantation revolution” had permanently reshaped the region: planters consolidated landholdings, expanded rice and indigo cultivation, and deepened a hierarchy defined by white dominance and Black subordination. After the American Revolution, South Carolina’s planter elite sought to rebuild their economy and reinforce racialized control.[11] To maintain control, the state strengthened slave codes and expanded patrol networks. Yet this same era saw rapid movement into the backcountry regions of Georgia and South Carolina. These sparsely settled areas, marked by competing jurisdictions and limited oversight, offered fugitives like Venture small but meaningful opportunities to evade recapture.[12]

For twelve months, Venture lived in eastern Georgia near Brier Creek in Burke County, harbored by Richard Heath.[13] Heath was a substantial landholder whose extensive holdings along Jobler Creek and the Savannah River were recorded in state surveys.[14] He also appeared in the Augusta Chronicle and Gazette in 1790 as a Wilkes County “defaulter”—someone who had failed to appear for required civic or militia duties—which brought him to the attention of local authorities.[15] Though Heath owned enslaved people himself, his choice to shelter Venture highlights the complex, sometimes contradictory social landscape of the early South, in which personal networks, local tensions, and unknown motivations could enable acts that ran counter to planter norms.[16]

Eventually Venture was captured and returned to McPherson by a man named William McNorrill, whose background remains unclear. Venture soon escaped again, this time reaching Abbeville County in the Ninety-Six district of western South Carolina. This region—deeply contested during the Revolution and marked by raids, property seizures, and militarization—was a perilous environment for a fugitive.[17]Venture remained there for six months with George Patterson, a small-scale householder who lived with his family and at least one enslaved person, before he was ultimately returned to McPherson.[18] These cycles of escape, refuge, and recapture illuminate how enslaved people navigated intensely surveilled landscapes, relying on fragile networks of protection wherever possible.

McPherson died at sea in 1806 when the ship Rose in Bloom wrecked en route from Charleston to New York.[19] His estate inventory listed the enslaved families still at Retreat Plantation—but not Venture.[20] His absence suggests he was never recaptured and that he ultimately succeeded in his pursuit of freedom. If so, Venture’s path diverged from that of most fugitives, marking him as a man who not only escaped but remained free. He may have found refuge in early networks later associated with the Underground Railroad, including the thick forests of Four Holes Swamp, which supplied food, shelter, and secrecy to freedom seekers.[21] He may have also reached Charleston’s harbor, where sites like Fort Moultrie and Fort Sumter would later become symbolic gateways to liberation.[22]

The only surviving words directly linked to Venture come from the advertisement that sought to reclaim him. Yet even through that hostile description, a clearer portrait emerges: Venture chose when to speak, strategically read his surroundings, escaped repeatedly, and carved out precarious spaces of autonomy. He was far more than “artful[ly] disposed” —he was a strategist who tested and transcended the limits of enslavement. His story reflects both individual resolve and the broader instability of his era, a moment when the contradictions between liberty and slavery were increasingly stark. Venture’s determination to claim freedom within this volatile landscape exposes the fragility of the plantation order and the enduring human drive to resist it.

View References

[1] Advertisement details drawn from, “Ten Guineas Reward,” The City Gazette (Charleston, South Carolina), February 14, 1792.

[2] Vincent Brown, Tacky’s Revolt: The Story of an Atlantic Slave War (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2020), 31-86, 90.

[3] Simon P. Newman, Michael L. Deason, Yannis P. Pitsiladis, Antonio Salas, and Vincent A. Macaulay, “The West African Ethnicity of the Enslaved in Jamaica,” Slavery & Abolition 34, no. 3 (2012): 394.

[4] Lynne Oats, Pauline Sadler, and Carlene Wynter, “Taxing Jamaica: The Stamp Act of 1760 & Tacky’s Rebellion,” EJournal of Tax Research 12, no. 1 (2014): 162–84, http://york.ezproxy.cuny.edu:2048/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.york.ezproxy.cuny.edu/docview/1567559060?accountid=151

[5] FamilySearch, “Prince William Parish, South Carolina,” FamilySearch, March 12, 2024, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Prince_William_Parish,_South_Carolina#cite_note-SCIWAY-2 [accessed December 15, 2025].

[6] Margaretta Childs and Isabella Leland, “South Carolina Episcopal Church Records,” The South Carolina Historical Magazine 84, no. 4 (October 1983): 263.

[7] N. Louise Bailey and Elizabeth Ivey Cooper, Biographical Directory of the South Carolina House of Representatives, Volume III: 1775–1790 (1981), 462–64.

[8] Heritage Library, “Washington-McPherson Connection,” Handwritten Letter, Heritage Library, n.d., https://heritagelib.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/McPherson19.pdf [accessed December 15, 2025].

[9] Watson Jennison, Cultivating Race: The Expansion of Slavery in Georgia (University Press of Kentucky, 2012), 42–50.

[10] Ira Berlin, Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America (Harvard University Press, 1998), 145-148.

[11] Berlin, Many Thousands Gone, 164-166.

[12] Ibid., 170-171.

[13] Dante Eubanks, “The Heath Enslaved History: Exploring the Heath Enslaved Relationships and Connection to William Heath of Surry County, Virginia,” Our Alabama and Georgia Ancestors, 24 Aug. 2017, https://ouralabamaandgeorgiaancestors.blogspot.com/2017/08/the-heath-slave-history-exploring-heath.html [accessed December 15, 2025].

[14] Richard Heath, Heath, Richard—Homes and haunts, Digital Library of Georgia, https://dlg.usg.edu/records?f%5Bsubject_personal_facet%5D%5B%5D=Heath%2C+Richard–Homes+and+haunts&only_path=true [accessed October 12, 2025].

[15] “A Return of Defaulters in Wilkes County, for 1790,” Augusta Chronicle and Gazette of the State, October 16, 1790, Image 4, https://gahistoricnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu/lccn/sn82015220/1790-10-16/ed-1/seq-4/ [accessed December 15, 2025].

[16] Eubanks, “The Heath Enslaved History.”

[17] Clayton Hensley, “Revolutionary War Battles & Skirmishes,” The Old 96 District – South Carolina, https://visitold96sc.com/revwar/ [accessed October 16, 2025].

[18] Robert Mark Sharp, “The Patterson Family Line,” RootsWeb, 9 Jan. 2004, https://sites.rootsweb.com/~sharprm/patterso.htm [accessed October 16, 2025].

[19] “Washington-McPherson Connection,” Handwritten Letter, n.d.

[20] “South Carolina Estate Inventories and Bills of Sale,” Estate Inventories, Book D (1800-1810), 1806, 421–23. https://lowcountryafricana.com/enslaved-ancestors-estate-john-mcpherson-sc-1806/ [accessed December 15, 2025].

[21] Shamira McCray, “3 More Lowcountry Sites Recognized by Parks Service for Connection to Underground Railroad,” The Post and Courier, February 1, 2022, https://www.postandcourier.com/news/3-more-lowcountry-sites-recognized-by-parks-service-for-connection-to-underground-railroad/article_ee7934c4-82ab-11ec-988e-e3b29232b734.html [accessed December 15, 2025].

[22] National Park Service, “Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie,” The Underground Railroad in Charleston Harbor (blog), n.d., https://www.nps.gov/fosu/learn/historyculture/the-underground-railroad-in-charleston-harbor.htm#:~:text=In%202023%20and%202024%2C%20two,during%20the%20American%20Civil%20War [accessed December 15, 2025].