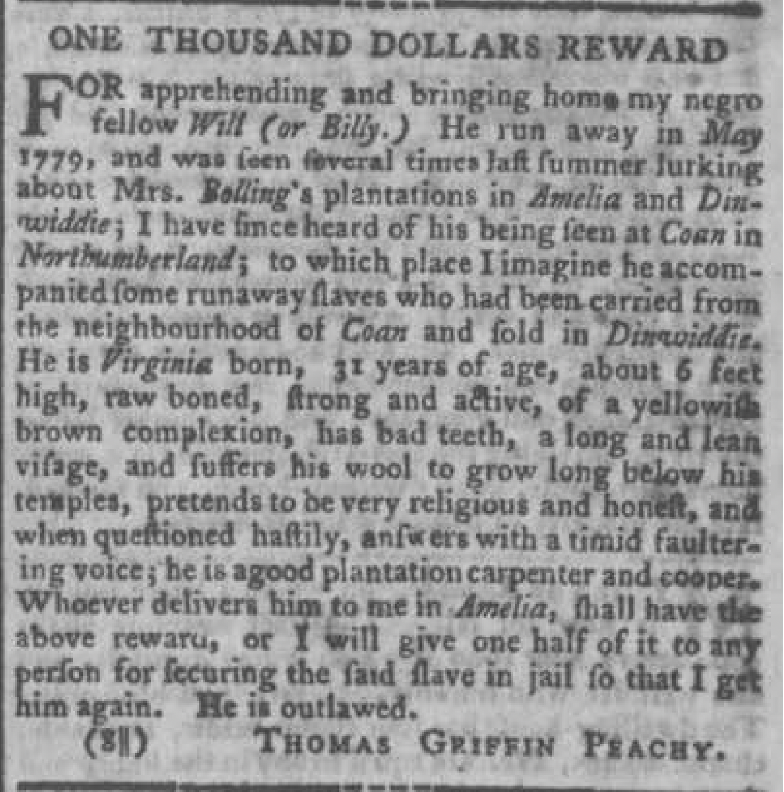

In a July 1780 edition of the Virginia Gazette, Thomas Griffin Peachy lashed out in a desperate bid to locate Will, a man he had enslaved. Will, who appears to have also gone by the name “Billy,” had been enslaved on Peachy’s plantation along the Rocky Run stream in Amelia County, Virginia. It was there that Will labored as a carpenter and cooper.[1] Peachy, like many slaveholders, sought to extract as much value from Will’s work as possible, even as he simultaneously undermined and devalued these skills in his “property.” This meant Peachy would acknowledge Will’s abilities while concurrently denigrating and dismissing them. He described Will, tellingly, as someone who tended to put on an act, often deceitfully. Will “pretends to be very religious and honest,” Peachy explained, and when questioned, tends to “hastily answer” with a “timid faultering voice.”[2] For Peachy, these habits showed that Will was untrustworthy and deceitful. But what Peachy interpreted as character flaws surely meant something very different to Will; indeed, these qualities may have been survival strategies. Will’s escape, along with his dynamic and complicated relationship with Peachy, together reveal the changing religious conditions and revolutionary ideals that were then actively reshaping Revolutionary-era Virginia.

Will escaped during a critical time and place in American history, one that was, and in many ways, foundational to the contradictions that would shape life in the early Republic. The American Revolution was a time of opportunity for the enslaved, especially in Virginia. In 1775, Governor of Virginia Lord Dunmore declared that any enslaved man who fought for the British would earn his freedom, leading many to escape to British lines. But Dunmore was not the only source of opportunity for Black Virginians.[3] Enslaved people in Virginia were also witnessing another social transformation that had been brought about by the rise of evangelicalism. This revivalist style of Christianity led by Methodists and Baptists, made inroads within enslaved communities, though often against the wishes of the Anglican Virginia gentry. Baptists in particular developed a counterculture that attracted Black worshipers by emphasizing personal spiritual experience through adult baptism as well as a sense of community. The most radical Baptists acknowledged the equality of all souls before God, which resulted in some churches allowing free Black and enslaved people to worship in what had previously been exclusively White spaces.[4] The rise of Black Christianity in Virginia thus challenged the racial order of planter society by destabilizing the relationship between freedom and Christian faith. Some Baptists even offered leadership roles for Black members. A number of freedom seekers during this time were even ministers to Black congregations.[5] As Rhys Isaac notes, efforts of wealthy planters like William Byrd to sell away Baptist converts ironically had the effect of contributing to the spread evangelicalism throughout Virginia.[6] Overall, the members of the gentry who were fighting for ideas of freedom also sought to regain control of the society they had dominated. Freedom seekers like Will, who Peachy even had declared an “outlaw”, further challenged planter society by escaping.

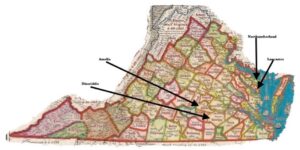

It was this world of revolutionary warfare and religious revival into which Will attempted to disappear. Will had been on the run for over a year before Thomas Peachy decided to advertise his escape. After escaping from Peachy in Amelia County in May, Will spent the summer of 1779 “lurking” around plantations belonging to the Bolling family (an established Virginian dynasty) located in Amelia and Dinwiddie counties.[7] As summer turned to fall, Will headed east. Information that Will was spotted around Northumberland County, near the mouth of the Potomac River, somehow made its way back to Peachy. The distance between Amelia and Northumberland was approximately eighty miles as the crow flies, but Will likely did not travel this way, making his journey significantly longer. Moreover, Peachy suspected that Will had not traveled alone but rather “in the company of some runaway slaves who had been carried from the neighbourhood of Coan and sold in Dinwiddie.”[8] We do not know how Peachy came by this idea or how he became aware of Will’s presence in Northumberland. Perhaps Will’s height, his distinctive long hair, or his “yellowish brown complexion” made him stand out. While Will managed to evade capture over such an incredibly long journey, the fact that Peachy still received tips as to his whereabouts highlights the challenge of escape in Revolutionary-era Virginia.

Religion was likely a source of tension between Peachy and Will. Peachy, who was part of the established Anglican church, implied that Will merely pretended to be Christian, and that his faith was an act.[9] Peachy’s dismissive comment echoes that of another Virginian enslaver from nearby Buckingham county, named Stephen Dence, who said of a freedom seeker named Hannah that “she pretends much to the religion the Negroes of late have practiced, and may probably endeavor to pass for a free woman.”[10] In this way, religiosity could indeed be a survival tactic for enslaved people like Will and Hannah to pass as free. But given the spread of evangelicalism among the enslaved, it is just as likely that Will’s faith was genuine.[11] Will’s possible Baptist faith exemplifies the spread of new religious ideas among groups seeking greater liberty in Virginian society. As a member of the Virginia establishment, Peachy might have viewed the Baptists and, therefore Will himself, as manifestations of the ongoing threats to the social order.[12] While elite Virginians like Thomas Jefferson would later champion religious toleration, religious freedom amongst the enslaved was not something that men like Peachy could countenance.

Will was ultimately recaptured in November of 1780 and held in a jail in Lancaster county. This does not, however, diminish his lengthy journey of attempted self-emancipation.[13] His attempt at freedom and lengthy period out of slavery demonstrates a significant contradiction between the ideals of the Revolution and the realities of slavery. This contradiction becomes evident when viewed from a different perspective. Much of Revolutionary-era history revolves around men like Jefferson or Washington but seldom highlights the people they enslaved. By centering Will, the American Revolutionary-era becomes one of great contradiction, where both political and religious freedom were unevenly distributed.

View References

[1] After the first publication of this advertisement on July 26, 1780, Thomas Griffin Peachy ran the advertisement four more times, on August 2, August 9, August 16, and September 13, all in the Virginia Gazette. For the location of Peachy’s plantation in Amelia County, Virginia see “TAKEN up at my plantation on Rocky Run, in Amelia,” Virginia Gazette, (Williamsburg, VA) March 14, 1777.

[2] “One Thousand Dollars Reward.” Virginia Gazette (Williamsburg, VA), July 26, 1780.

[3]Douglas R. Egerton, Death or Liberty: African Americans and Revolutionary America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009) 69-72.

[4] Rhys Isaac, The Transformation of Virginia, 1740–1790 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 171. Thomas S. Kidd, “The Great Awakening in Virginia.” Encyclopedia Virginia, June 10, 2025. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/great-awakening-in-virginia-the/ [accessed December 8, 2025].

[5] Isaac, The Transformation of Virginia, 172; Philip Morgan, Slave Counterpoint: Black Culture in the Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake & Lowcountry (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998) 652.

[6] Ibid., 172.

[7] “Mrs. Bolling’s plantations in Amelia and Dinwiddie” very likely refers to the holdings of the Colonel Robert Bollings, who represented Dinwiddie County in the Virginia Assembly and was a major landholder. He had died in 1775, leaving his widow who Peachy mentioned in the advertisement. See for example, “TAKEN up on the Subscriber’s plantation… an old white HORSE… Robert Bolling, junior.” Virginia Gazette (Williamsburg, Virginia) December 10, 1772.

[8] “One Thousand Dollars Reward.” Virginia Gazette (Williamsburg, VA), July 26, 1780.

[9] Thomas Griffin Peachy married Elizabeth Mills on September 22, 1783 in Christchurch, Middlesex Virginia, which was an Anglican church before the Revolution. See The Parish Register of Christ Church, Middlesex County, VA. From 1653 to 1823 (Richmond: WM. Ellis Jones Steam Book and Job Printer, 1897), 209 https://archive.org/details/parishregisterof00chri/page/208/mode/2up?q=peachy [accessed December 17, 2025].

[10]“N.B. Run away…Hannah,” Virginia Gazette (Williamsburg, Virginia) March 26, 1767, quoted in Philip Morgan, Slave Counterpoint: Black Culture in the Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake & Lowcountry (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998) 427.

[11] Kidd, “The Great Awakening in Virginia.”

[12]Thomas Griffin Peachy to Thomas Jefferson, 3 September 1793,” Founders Online, National Archives and Records Administration, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-27-02-0027 [accessed September 25, 2025].

[13] “COMMITTED to the Jail of Lancaster County, a negro man named Will, ” Virginia Gazette (Williamsburg, Virginia), November 18, 1780.