He was an African, his heritage visible for all to see in his dark colored skin and the ritual scarification on both sides of his face, a West African practice that was not replicated in the Americas. We do not know when he was trafficked to the Americas, or how he came to be in Rhode Island. The Brown Family in Rhode Island were deeply invested in the trans-Atlantic slave trade, often transporting enslaved people to the British Caribbean, the Carolinas, or the Chesapeake, and then bringing the crops grown by enslaved people to Rhode Island. Occasionally enslaved people were transported with this produce, and perhaps Yockwhy had crossed the Atlantic in a ship like the Sally, based in Providence and owned by four members of the Brown family. In October 1765 the Sally sold 92 enslaved Africans in Antigua, but perhaps on this or a similar voyage Yockwhy sailed up the eastern seaboard and was then handed over to the Brown family.[1]

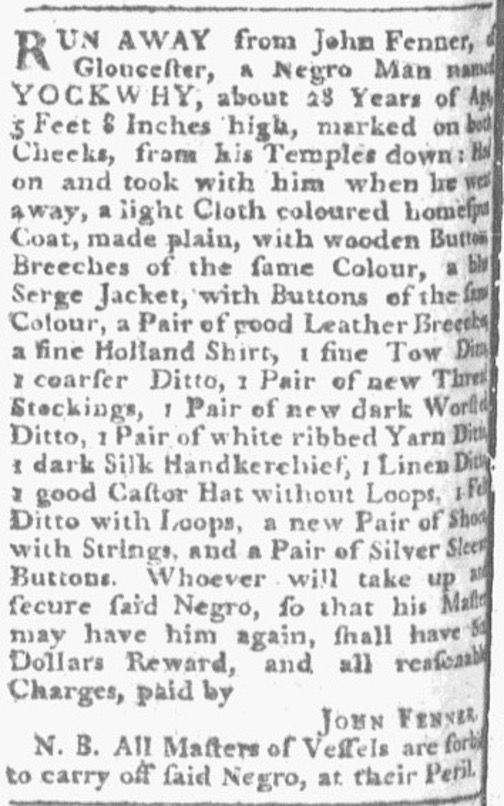

Nine years later Yockwhy was quite likely an enslaved servant in the household of John Fenner, in Glocester, a small town about twenty miles north-west of Providence. Fenner was the son-in-law of Obadiah Brown, and perhaps Yockwhy had come to Fenner through this familial connection. Made up of nine people, the Fenner household was one of the largest in Glocester, as recorded in the 1774 Rhode Island census. Three of these were listed simply as “Blacks,” probably including Yockwhy.[2] As the American independence movement began loosening the bonds of slavery, Yockwhy saw and seized his opportunity, escaping in the late Fall of 1777. He took with him not just the clothes he was wearing, but what may well have been his entire wardrobe. Taking such a large quantity of clothing may indicate premeditation, and a desire to sell and barter some clothing both to raise funds and to disguise his appearance. Fenner responded to Yockwhy’s escape by placing lengthy advertisements in the Providence Gazette, as well as in the Massachusetts-Spy and the Connecticut Courant.[3]

It is unclear whether Yockwhy’s bid for freedom was immediately successful. But even if Fenner was able to recapture Yockwhy, it was at best a short-term victory for the enslaver. Even though the Federal census of 1790 recorded that Fenner’s household had increased to eleven people, ten were White with an eleventh recorded as a free person of color. This was not Yockwhy, for the same census recorded that he had become a head of household himself in Providence, along with one other free person of color.[4] Yockwhy’s escape in 1777 had surely helped secure this new status. The fact that Yockwhy had taken and was living openly with the name Fenner suggests that he had won his freedom, either through self-liberation acknowledged by John Fenner, or by one of the many acts of emancipation by White Rhode Islanders during these years. In 1790 John Fenner’s brother Arthur became governor of Rhode Island, making this a very recognizable name: Yockwhy would likely have remained in Providence under this name only if his freedom was secure.[5]

Who was the other person in Yockwhy Fenner’s household in 1790? It may have been his wife or partner, but another record suggests that perhaps this person was his son. The membership lists of the First Baptist Church in Providence recorded that on March 22, 1789 both Yockey Fenner and Sambo Fenner had become members of the church. Interestingly, both were recorded as securing membership by means of a letter attesting to their prior membership in another church, although there is no record of which church this was.[6] If Sambo was Yockey’s son, then who was his mother, and where was she? Perhaps she was still enslaved, and this explained why she was not a member of their household: the 1790 Federal census recorded 47 enslaved people in Providence, with more in the surrounding towns. Alternatively, she may have been sold or have died, which might explain why Sambo was with his father rather than with his mother and her enslaver.[7]

Although born in Africa, Yockey Fenner had made Rhode Island his home. Once he achieved freedom he did not leave the colony, and instead he settled in Providence just a few miles from the site of his former enslavement. By 1790 Rhode Island was home to more than 3,400 free people of color, 427 of them in Providence.[8] Yockey and Sambo Fenner were members of and helped form that community, as often happened in post-Revolutionary America.

View References

[1] Voyage of the Sally, Voyage 36299, Slave Voyages: Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database [accessed November 25, 2024].

[2] Entry for John Fenner, Glocester, Rhode Island in Census of the Inhabitants of the Colony of Rhode Island and providence Plantations, Taken By Order of the General Assembly, In The Year 1774, arranged by John Bartlett, (Providence: Knowles, Anthony & Co., 1858), 132.

[3] “RUN AWAY from John Fenner, of Gloucester, a Negro Man named YOCKWHY,” Providence Gazette; And County Journal, October 4, 1777, repeated October 11, 18; Massachusetts-Spy, or, American Oracle of Liberty (Worcester, MA), October 30, 1777; The Connecticut Courant, and Hartford Weekly Intelligencer (Hartford, CT), November 4, 1777.

[4] Entry for John Fenner, Glocester, Providence County, Heads of Families At the First Census of the United States in the Year 1790. Rhode Island (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1907) 30; entry for Yockey Fenner Providence, Heads of Families At the First Census of the United States in the Year 1790. Rhode Island (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1907), 34.

[5] The Biographical Cyclopedia of Representative Men of Rhode Island (Providence: National Biographical Publishing Co., 1881), 136-7.

[6] Historical Catalogue of the Members of the First Baptist Church in Providence, Rhode Island, ed. Henry Melville King (Providence, RI: F.H. Townsend, 1908), 30.

[7] Entries for Providence, Heads of Families At the First Census of the United States in the Year 1790. Rhode Island (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1907), 33-7.

[8] Heads of Families At the First Census of the United States in the Year 1790. Rhode Island (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1907), 8-9.