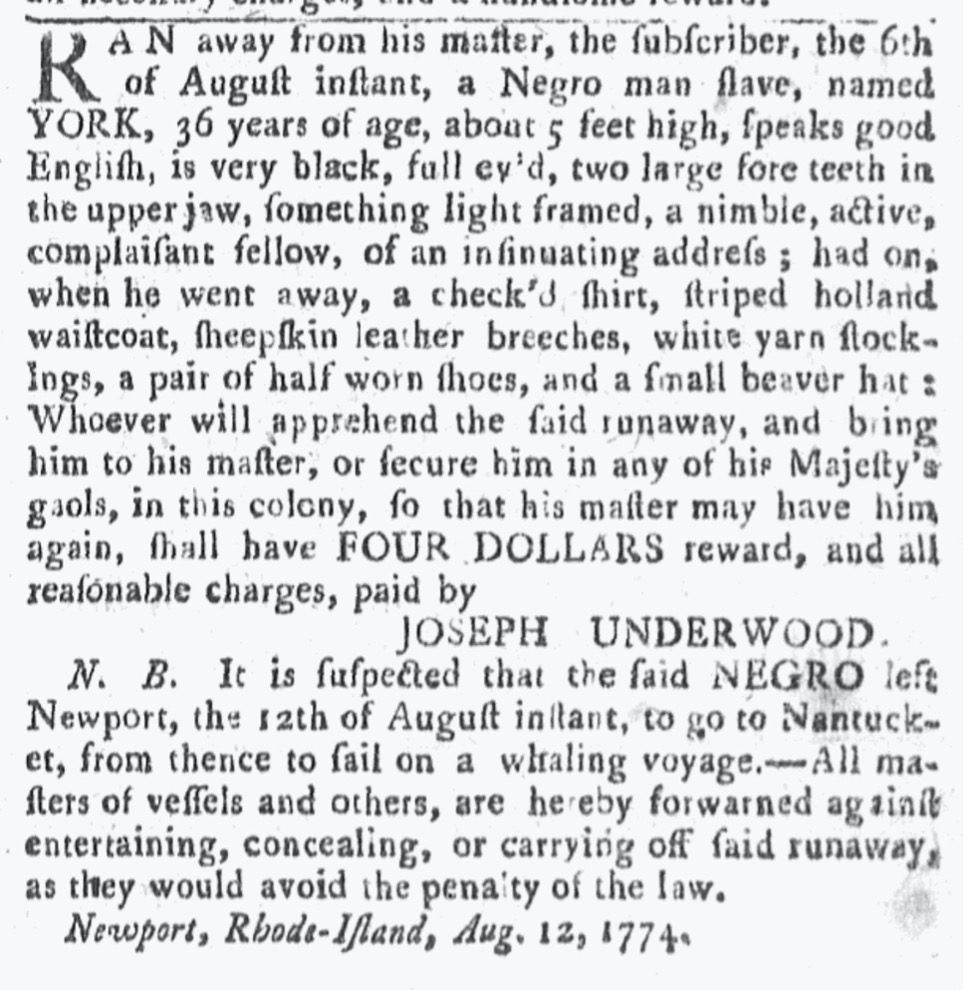

It is not surprising that York and other freedom seekers hoped to join the crews of New England’s whaling ships. Often desperate for new hands, whaling ship captains proved more than willing to sign up Black men with little or no maritime experience, even if the captains suspected the men of having escaped enslavement. In 1769, for example, Prince Boston signed on to the Nantucket whaler Friendship. Elisha Folger, a Nantucket whaling captain who was an anti-slavery Quaker, recruited Boston, even though he knew the man had escaped from William Swain, a Nantucket merchant and Prince Boston’s enslaver. Swain sued Folger, but was unsuccessful.[1]

Crispus Attucks was another whaler who may well have escaped from slavery. In 1750 a twenty-seven year-old “Molatto Fellow” named Crispas had eloped from William Brown in Framingham, Massachusetts. It is an unusual name, and it is possible and perhaps even likely that this man of African and indigenous heritage escaped and joined a ship. Over the following twenty years he likely worked on different kinds of ships, and contemporary accounts indicate that these included whaling ships. When he died in the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770, Attucks had likely lived almost half of his life as a free sailor.[2]

Whether legally free or not, Black sailors faced harsh working conditions, disease and the risk of serious injury or death, and were paid low wages. Whaling was perhaps the most challenging of oceanic occupations, with crews facing voyages that might take years, on smaller and often poorly equipped ships. Many skilled sailors tended to avoid whaling, and the crews of ships leaving Nantucket, New Bedford and other whaling tows were often a motley assortment of greenhands. In fact, the New England whaling industry featured one of the most racially and ethnically diverse workforces of the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries. White, Black, and Indigenous Americans labored besides European, Azorean, Cape Verdean, Peruvian, Pacific Islanders and Asian mariners.[3]

Freedom seekers were clearly able to capitalize on the constant demand for sailors in New England’s ever-growing whaling industry. Over time the Black community in Nantucket and New Bedford grew, and a few Black whalers such as Absalom F. Boston (the nephew of freedom seeker Prince Boston) and Edward J. Pompey rose through the ranks to become captains. Situated some thirty miles off the Massachusetts coast, Nantucket may have felt sufficiently distant from the North American mainland to give freedom seekers and their community a sense of security. The section of Nantucket populated by Black residents was commonly known as Guinea, or New Guinea. Frederick Douglass delivered his first formal speech in support of the abolition of slavery in Nantucket in 1841, which by that time was a community shaped in part by generations of freedom seekers turned whalemen. At the time Douglass lived in New Bedford, where he had gone because those who aided his escape suggested that his skill as a caulker could lead to steady work in the whaling industry.[4]

If York succeeded in making his way to Nantucket in 1774, he would have found a whaling fleet of some 150 ships, employing more than 2,000 crewmen, and annually harvesting 26,000 barrels of sperm whale oil and 4,000 barrels of right whale oil.[5] Surely York would have found his way onto one of these ships, just like Prince Boston and Crispus Attucks? Whaling voyages were long and arduous, perhaps lasting as long as two years. York and his fellow sailors would have been paid under the “lay system,” whereby the ship owners received about one-third of the profits from the sale of whale oil, another third covered the costs of the voyage, while the final third was divided among crew members. This did not usually translate to high wages, and skilled workers on shore or on other merchant vessels typically earned more, but whaling may well have been one of the most accessible careers to male freedom seekers in late eighteenth-century New England.[6]

As historians like W. Jeffrey Bolster have demonstrated, although race and racism never disappeared the challenges of work at sea pulled seafarers together. While sailors’ pay was low, Blacks and Whites often earned the same, including the “lays” or shares of whalemen. Some Black whalemen were able to purchase homes and establish families, although they were often at sea far more than at home. Their work was hard, in foul-smelling and dangerous conditions, and generally more poorly paid than merchant shipping. And yet “there is,” observed one commentator, “no barrier, no dividing line, no complexional distinction, to hedge up the cabin gangway or the quarter-deck, to prevent the intrepid, enterprising, and skillful coloured sailor from filling the same station as the white sailor, but all are alike eligible, and stand upon a common level.” For male freedom seekers in New England, whaling promised greater freedom and equality that they would never know on land.[7]

View References

[1] “Free Negroes and Mulattoes,” A Report of the Massachusetts House of Representatives (Boston: True and Green, 1821), 11-12.

[2] “RAN-away… a Molatto Fellow… named Crispas,” The Boston Gazette, Or Weekly Journal (Boston), October 2, 1750. The advertisement was reprinted November 13 and 20, 1750. See also Mitch Kachun, First Martyr of Liberty: Crispus Attucks in American Memory (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 7-28.

[3] James Farr, “A Slow Boat To Nowhere: The Multi-Racial Crews of the American Whaling Industry,” The Journal of Negro History, 68 (1983), 159-70; Eric Jay Dolin, Leviathon: The History of Whaling in America (New York: W.W. Norton, 2007), 223; Jennifer Schell, “‘I Was Now Living in a New World’: Frederick Douglass, Herman Melville, and New Bedford’s Cosmopolitan Locality,” in Edward Watts, Keri Holt, and John Funchion, eds., Mapping Region in Early American Writing (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2015), 162.

[4] Justin Andrew Pariseau, “Sea of Change: Race, Abolitionism, and Reform in the New England Whale Fishery,” M.A. Thesis, College of William and Mary, 2005, 3, 1. Frederick Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom (New York: Miller, Orton, and Mulligan, 1855), 340-1.

[5] Alexander Starbuck, History of the American Whale Fishery (Secaucus, NJ: Castle Books, 1989), 128.

[6] Pariseau, “Sea of Change,” 42-5.

[7] William P. Powell, “Coloured Seamen—Their Character and Condition, No. IV, Statistics of Coloured men—Captains and Officers of Merchants and Whaling Vessels,” National Anti-Slavery Standard, Issue 22, October 29, 1846. See also W. Jeffrey Bolster, Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1997), 207; 68-9, 161, 165, 176-9.