Name Unrecorded (November 1767)

The Clothes That He Wore

By Ellanora LoGreco

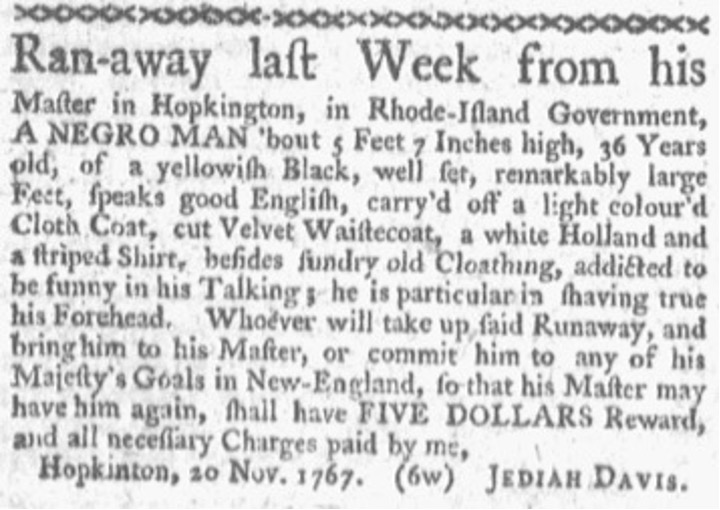

The clothes he was wearing when he escaped are the most memorable things about the man who is the subject of this advertisement. Not even a name is recorded. There is nothing in the archive to reveal more about this man and his life besides the scant facts his enslaver Jediah Davis chose to share. Slavery and its afterlives have continuously buried the lives of Black folks through an archive that records only what white, landowning men wished to say. Reconstructing the clothing that he wore is a project aimed at bringing some sense of this particular man out of the archival silence in which he exists presently. Therefore, I invite you to sit with the clothes – touch them, if you can – and try to be shaped by their story.

Reconstruction or recreation of historical clothing allows the maker to tap into a tactile and sensory form of engagement with a historical moment. The research becomes not just about asking why the man in this advertisement may have been wearing these clothes, but understanding the haptic knowledge obtained from the making and wearing of the clothing. And wearing the reconstructed clothes – or even just touching them – aids in tapping into the original wearer’s “enclothed cognition.” This may partially illuminate moments of his life – like the symbolic and physical experience of wearing specific items of clothing – not defined or limited by the words of his enslaver.[1] The process is not about bringing the man back to life or pretending to be in his shoes or the shoes of the tailor who made these clothes. Rather, the goal is to bring fragments of a life out of archival silence through a reconstruction process that taps into the complex interplay between maker and wearer. I hope the completion of this project and the display of this clothing can serve to allow others to grasp the importance of seeing and feeling this clothing, not just reading about it, and allow engagement with the material world of this man.

The garments that this man wore were not a laborer’s working clothes. As Simon Newman has explained in his Freedom Seeker story, they could have been taken from his enslaver to help the freedom seeker pass as free, or perhaps to be sold or traded. Alternatively, they may have been acquired by this man, likely second-hand. It also was not uncommon for enslavers to give higher quality clothing to enslaved personal servants as a way to publicly display the enslaver’s wealth and status. The pieces of the ensemble reconstructed here are a linen shirt, velvet waistcoat, and fall-front knee breeches.[2] While the waistcoat and breeches are designed to accommodate the physical activities of daily life for eighteenth century men, they were close fitting and were not meant for hard labor.[3] Such clothes would have been sewn by skilled tailors who patterned garments to custom fit the body. It is highly unlikely that these were custom made for this enslaved man and so there was no direct contact between maker and wearer. Yet, a connection exists through this freedom seeker’s engagement with a larger making process and economic system through a piece of material culture that was handmade to create a certain wearing experience.

A tailor in 1767 would have known how to sew a tight backstitch, cut linen straight, and perfectly fit a waistcoat to fit snugly over a shirt and under a close-cut coat.[4] Many of the techniques used are not present in modern garment construction and the construction of the breeches was the piece of the project that was most directly at odds with modern patternmaking. Breeches are not specifically mentioned in the advertisement, but they were a standard garment for the period. I was able to create a pattern contemporary to 1767 through use of a historical and theatrical tailoring book and examination of extant breeches at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) Museum.[5] Knee breeches are sewn together in a manner similar to modern pants, but rather than constructing a zipper fly, the front of the pants is an intricate puzzle of overlapping pockets, flaps, and button tabs (Fig. 1). The fall front, which became popular in the latter half of the eighteenth century as waistcoats shortened, must be cut and lined smoothly before the linen pockets can be inserted, which must in turn happen before the waistband can be attached and the buttons added.[6] The breeches were constructed out of Burnley and Trowbridge’s reproduction wool broadcloth,[7] which is sturdy and warm and was very common for trousers and breeches during this period along with leather and heavy cottons.[8] The fabric is heavy and hot and it was difficult to maneuver the needle through small enough sections of the material to sew the tiny, tight backstitches the project required. It was even more difficult to align the smooth, thin linen that lines the fall front with the heavy broadcloth. These are processes based very much in an understanding of how the hand should move the fabric and would only get easier with time and experience. What challenged me would have been routine for an eighteenth-century tailor.

Sewing the shirt and waistcoat was similarly challenging. It took hours for my hands to figure out how they should be oriented, something an eighteenth-century tailor would have known and done without a second thought. I struggled to keep my coarse linen thread from straining the delicate silk lining of the waistcoat and to keep the silk from bubbling as I attached it to the much heavier Manchester velvet of the front of the garment.[9] The waistcoat, like the breeches, is a garment that would have been sewn by a tailor to custom fit the wearer. My pattern came from extant examples in the RISD Museum and the patterns developed in the same theatrical and historical tailoring book used for the breeches pattern.[10] The garment is made up of two purple velvet front pieces, lined with lightweight golden silk, and two back pieces made of a double layer of silk. The back is made of the lining fabric because in most formal situations a coat would have been worn over the waistcoat, making the back invisible. The plush, expensive velvet is saved for the always-seen front.

The shirt is a simple linen undergarment that would have been owned and worn by most men during this period. Many extant examples, like those in the RISD Museum’s collections, have ruffles on the collars and cuffs for decoration. These however would impede movement and labor so would not have been added to shirts worn by someone working, even as a domestic servant or attendant. The linen shirt is meant to sit next to the body and be washed frequently, as it is the layer that absorbs sweat and protects the outer clothes from bodily stains. Because of this frequent washing, areas where the fabric splits on the neckline and cuffs and where the arm attaches to the body are reinforced with patches (Fig. 2). The whole garment is tightly backstitched for increased durability.

The clothing in this ensemble is shaped in ways very unfamiliar to wearers of modern clothing, yet this “strangeness” was by design and directly informed by the function of the garment. Knowing what the garment was used for is what actually allowed me to create contemporary patterns by working backwards, so to speak. An eighteenth–century tailor would have made these clothes with the knowledge that clothing is always a negotiation between maker and wearer, informed by the wearer’s needs. The freedom seeker in the advertisement entered into this negotiation by wearing these clothes, working and traveling in them, and using them for what they were constructed for, even though they hadn’t been constructed for him. A linen undershirt is perhaps the most familiar shape in the ensemble and the reason for its particular form is that the shirt is constructed entirely out of rectangles of linen (Fig. 3). The garment has no seam across the shoulders and a very wide neck hole is gathered into the collar creating a particular shape that slides back and forth over the shoulders and allows most any movement.[11] The signature drape of the shirt is dependent on the rectangles, meaning the linen must be cut perfectly straight. Linen is very slippery so to cut straight, a single thread is drawn out of the weave leaving a gap on which I could cut. The shirt fits snugly underneath the slim waistcoat despite being made of so much more fabric than the outer layer. This is because the waistcoat takes a complementary shape. The armscye is wide but set back in the garment and the chest has ample room (Figs. 4, 5).[12] This has the effect of forcing the wearer to stand up straight with the chest pushed forward, lest the garment look wrinkled and ill–fitting. When the waistcoat was off, the linen shirt could become looser fitting pajamas.

The fall front breeches and their many thread-wrapped buttons appear where the waistcoat opens on its lower half.[13] Thread-wrapping is a simple, but time–consuming technique that covers wooden button molds in silk button hole thread giving them a woven, satin finish (Figs. 6 & 7). The back of the breeches are cut very wide at the top and then gathered into the waistband so as to allow ample room around the bottom for ease of movement. This gives the wearer the ability to sit comfortably atop a horse for long periods of time without straining the fabric and while maintaining a flexible and comfortable fit around the crotch. Additionally, while these breeches were practical for everyday wear, they would usually be worn under simply cut, coarse linen work trousers to protect them during any hard labor.[14] The ensemble holds the wearer in a certain posture – not unnatural, just unfamiliar to a modern clothes-wearer – that this man would have been intimately familiar with. However, it is entirely possible that his clothes didn’t fit him quite right, on account of them being second-hand, so perhaps the posture they held him in wasn’t the same as it would’ve been for the original owner.

It is impossible to say how this man felt inside these clothes, but it is possible to reconstruct the clothes, feel them, and understand their purpose. By experiencing the making-process of these three garments, I have gained an increased understanding of the negotiation between tailor and wearer and as a result, the way it felt to wear these clothes, and why they felt this way. Seeing his lush purple waistcoat paired with his everyday brown breeches conjures the image of a man who in addition to taking care with the appearance of his hair wished to dress in soft velvet, picked out the colors he wore, and cared for his clothing to keep it fine. By experiencing clothing like that which he wore we can learn something of his sensory experience of being clothed, both in his daily work and as he walked towards freedom. For a moment, we can learn something more about the life of a man whose name is no longer known who escaped from slavery more than two hundred and fifty years ago.

View References

[1]Hilary Davidson, “The Embodied Turn: Making and Remaking Dress as an Academic Practice,” Fashion Theory 23, no. 3 (2019): 346

[2]Fall front knee breeches are a style of breeches where the opening at the front (the “fall front”) is constructed with a flap that buttons to the waistband and opens downward to let the wearer in and out of the garment. The breeches reach to just below the knee, where they are tightly fastened.

[3]Linda Baumgarten, What Clothes Reveal: The Language of Clothing in Colonial and Federal America : The Colonial Williamsburg Collection, with Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg Decorative Arts Series. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in association with Yale University Press, New Haven, 2002). 122

[4] A backstitch is the strongest hand sewing stitch for sewing seams. For each stitch forward the thread is looped backwards over the same area for extra strength.

[5] Graham Cottenden, 18th Century Male Tailoring: Theatrical and Historical Tailoring C1680-1790 (Routledge/Taylor and Francis Group, 2024).

[6] Baumgarten, What Clothes Reveal, 226-229.

[7] Broadcloth is a very tightly woven wool textile with a silky and flannel-like finish. It is woven tightly enough that it does not fray or unravel upon cutting, meaning the raw edges don’t need to be finished. Burnley and Trowbrige describes this particular material as “a superfine broadcloth with a firm hand.”

[8] Baumgarten, What Clothes Reveal, 125

[9] Manchester velvet is a fine cotton velvet, popularized in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

[10] Cottenden, 18th Century Male Tailoring.

[11] Gathering is the process by which a length of fabric is bunched together by drawing a wide stitch through it which is then pulled on and results in the fabric being gathered together. The process has the effect of creating volume or, when gathers are particularly dense, ruffles.

[12] An armscye is the opening on the bodice of a garment where the sleeves are attached. Eighteenth-Century garments for both men and women tend to have armscyes that are shallow on the front piece of the garment and cut deeper toward the shoulder blades on the back piece, which pulls the wearer’s shoulders back and together slightly.

[13] Also called deathshead buttons, these woven-finished buttons appeared on many of the extant shirts and breeches I looked at for this project.

[14] Baumgarten, What Clothes Reveal. 126.

Image Gallery

Take a closer look Ellanora’s artwork by clicking on the images below.